Sheet Music For Traditional Irish Tunes On The Tin Whistle

The below are a few of the most popular ''Tunes'' that are played at sessions. The vast majority are worked out for a tin / penny whistle in the key of D and are generally Irish in origin. I will be adding more to this section over time.The below are a few of the most popular [ national melodies ] ''Tunes'' that are played at sessions. The vast majority are worked out for a whistle in the key of D. I will be adding more to this section over time.

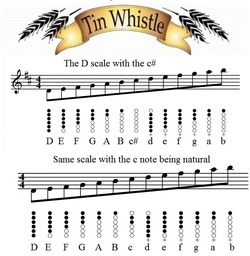

To play tunes by ear or to read the sheet music ? That's a question I have read on many's an internet forum. Players seem to be split in their opinion. There are those who feel you should never use sheet music for playing any kind of music, never mind traditional Irish tune. Those are the one's who have a natural gift of being able to play by ear and don't seem to grasp that playing notes doesn't come ease to the majority of musicians. So those who say you should only play by ear would exclude anybody who hasn't got that gift ? In that case their would be millions of people around the world who would never get the chance to enjoy playing a musical instrument. My view is that if sheet music helps then one should use it, that person over time will develop an ear and will gain an understanding of keys and if a piece of sheet music is put in front of them they'll be able to play it where as if the same sheet was put in front of the person who only plays by ear, , well they may as well be looking at a hedge. If the traditional tunes here seem a little bit difficult for you then check out the folk music for tin whistle, which you'll surly have some of the songs already floating about in your head .

To play tunes by ear or to read the sheet music ? That's a question I have read on many's an internet forum. Players seem to be split in their opinion. There are those who feel you should never use sheet music for playing any kind of music, never mind traditional Irish tune. Those are the one's who have a natural gift of being able to play by ear and don't seem to grasp that playing notes doesn't come ease to the majority of musicians. So those who say you should only play by ear would exclude anybody who hasn't got that gift ? In that case their would be millions of people around the world who would never get the chance to enjoy playing a musical instrument. My view is that if sheet music helps then one should use it, that person over time will develop an ear and will gain an understanding of keys and if a piece of sheet music is put in front of them they'll be able to play it where as if the same sheet was put in front of the person who only plays by ear, , well they may as well be looking at a hedge. If the traditional tunes here seem a little bit difficult for you then check out the folk music for tin whistle, which you'll surly have some of the songs already floating about in your head .

Below is the list of sheet music and tin whistle songs that are in my ebooks. This is the largest collection of tin whistle songs ever put together.[over 700 songs ] Including folk, pop and trad tunes plus German And French songs along with Christmas Carols.

All of the songs have been made as easy to play as was possible.

The price of the ebooks is €7.50 and will be emailed to you after payment. Please be patient.

All of the songs have been made as easy to play as was possible.

The price of the ebooks is €7.50 and will be emailed to you after payment. Please be patient.

Below is a list of the most popular Traditional Irish Tunes for tin whistle which comes free when you

buy the tin whistle ebook .

buy the tin whistle ebook .

I get sent many emails from people who have stated that they recently took up playing the tin whistle, some are aged over 80 years old and said that without the music notes on this site they would not have continued playing the whistle. This is very gratifying to hear and I'm delighted to be able to help out.

So what about the pop music section on the site ? I was very hesitant about setting up this section. I really hadn't a clue if it would be popular or if I was wasting my time. So I took a chance and put a good mixture of old and new songs. It has really taken off and is now as popular as the folk songs. I had been playing some of these songs for years and if I was willing to play popular music on a tin whistle then there had to be many more like me. You see the whistle has always been associated with traditional Irish music and if you said to someone that you played a whistle they automatically assumed you were into trad. They would never think you played anything other that traditional or folk songs. One other reason for setting up the pop song section for tin whistle was to make the instrument more mainstream.

Learning Traditional Tunes - The advice I gave in the folk songs section about getting these tunes into your head is pretty much the same for trad. tunes. I think learning how to play songs on the whistle is much easier as the melody of the songs will already be in your head from years of listen to ''Dirty Old Town'' for example. My advice on these tunes is to learn one line at a time, it doesn't matter if it takes you all day to get the first line off by heart. The next day get the second line off even if it takes 100 tries. Then put the first and second together and so on. By the end of the week you'll be able to play the tune off by heart. Some people write to me asking if I have any easier versions of a tune as they are finding it too hard to play. When I ask how much long they watch television for compared to learning your tin whistle then the reason they find the tune hard to play becomes apparent. Too much television and not enough practise.

So what about the pop music section on the site ? I was very hesitant about setting up this section. I really hadn't a clue if it would be popular or if I was wasting my time. So I took a chance and put a good mixture of old and new songs. It has really taken off and is now as popular as the folk songs. I had been playing some of these songs for years and if I was willing to play popular music on a tin whistle then there had to be many more like me. You see the whistle has always been associated with traditional Irish music and if you said to someone that you played a whistle they automatically assumed you were into trad. They would never think you played anything other that traditional or folk songs. One other reason for setting up the pop song section for tin whistle was to make the instrument more mainstream.

Learning Traditional Tunes - The advice I gave in the folk songs section about getting these tunes into your head is pretty much the same for trad. tunes. I think learning how to play songs on the whistle is much easier as the melody of the songs will already be in your head from years of listen to ''Dirty Old Town'' for example. My advice on these tunes is to learn one line at a time, it doesn't matter if it takes you all day to get the first line off by heart. The next day get the second line off even if it takes 100 tries. Then put the first and second together and so on. By the end of the week you'll be able to play the tune off by heart. Some people write to me asking if I have any easier versions of a tune as they are finding it too hard to play. When I ask how much long they watch television for compared to learning your tin whistle then the reason they find the tune hard to play becomes apparent. Too much television and not enough practise.

Below is a list of over 170 traditional tunes with guitar chords in an ebook.

It cost €6.50

It cost €6.50