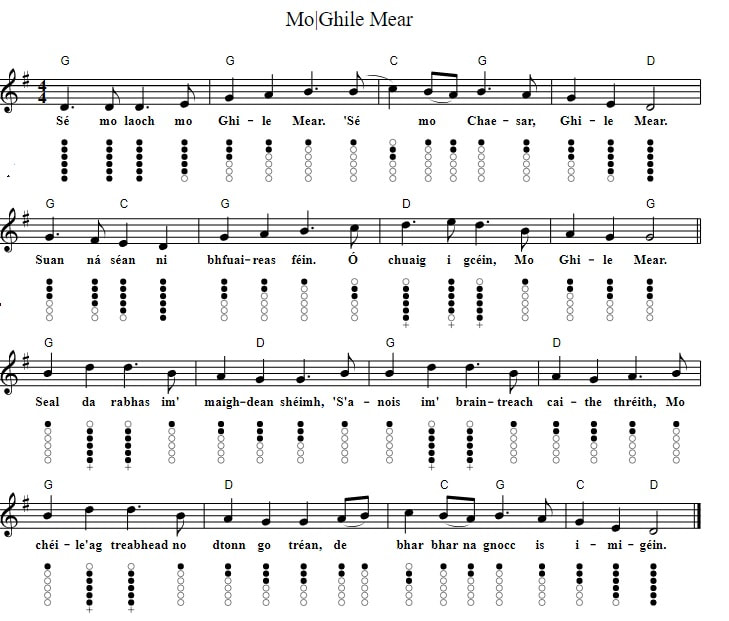

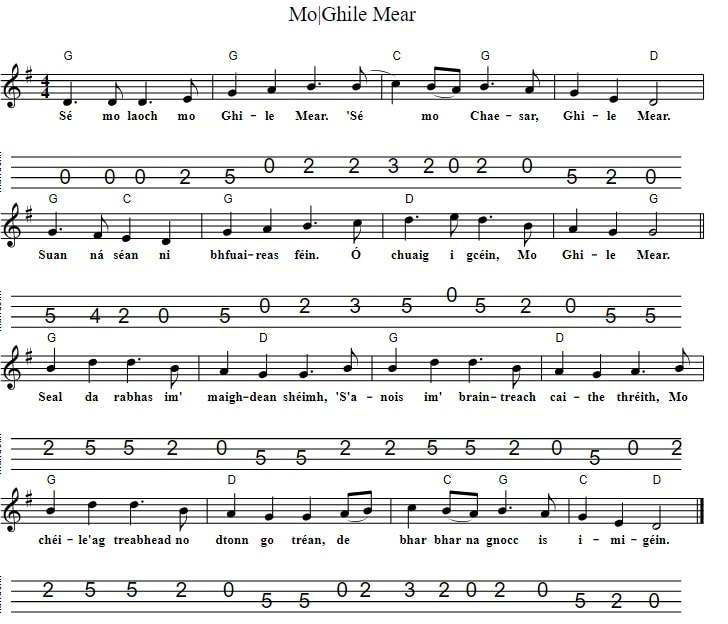

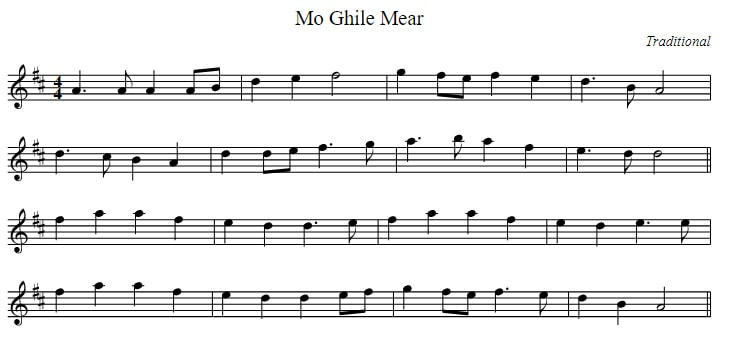

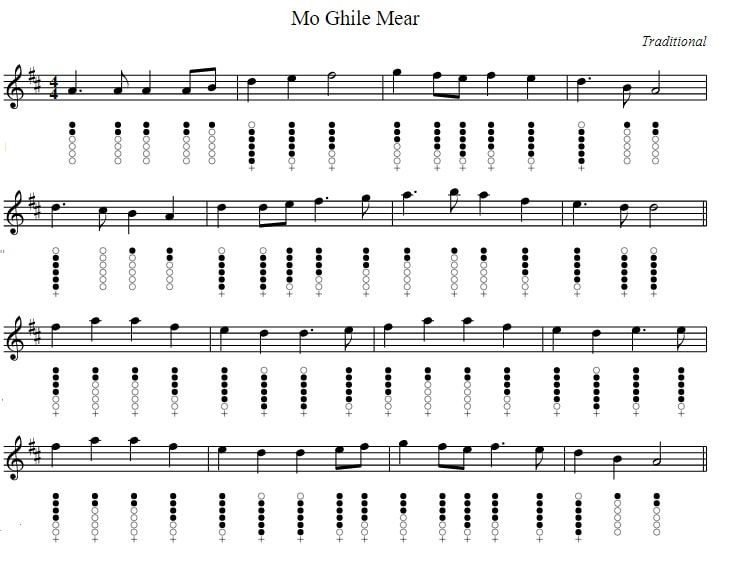

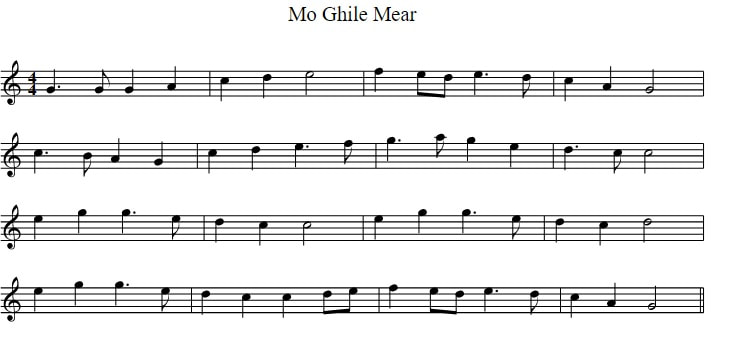

Mo Ghile Mear Sheet Music And Tin Whistle notes

MO GHILE MEAR / MY GALLANT DARLING Lyrics And Chords with sheet music and piano chords, plus tin whistle notes and mandolin tab . Recently recorded by Choral Scholars of University College Dublin, Celtic Thunder. (Seán Clárach Mac Domhnaill)

Traditional Songs in Irish-Gaelic language. Also translated ‚The Dashing Darling’.

For YouTube version of the Highland Sessions by Mary Black, Iarla Ó Lionáird, Mary Ann Kennedy, Karen Matheson, Karan Casey and Allan MacDonald use capo on 3rd fret.Guitar chords by Marc Fahrbach.

Note: the 1st verse uses the melody of the chorus an thus differs from the other verses. The Highland Sessions use an additional verse (sung by Karan Casey) between the verses 4 and 5 from below. The 6th verse given here was not used in return

Traditional Songs in Irish-Gaelic language. Also translated ‚The Dashing Darling’.

For YouTube version of the Highland Sessions by Mary Black, Iarla Ó Lionáird, Mary Ann Kennedy, Karen Matheson, Karan Casey and Allan MacDonald use capo on 3rd fret.Guitar chords by Marc Fahrbach.

Note: the 1st verse uses the melody of the chorus an thus differs from the other verses. The Highland Sessions use an additional verse (sung by Karan Casey) between the verses 4 and 5 from below. The 6th verse given here was not used in return

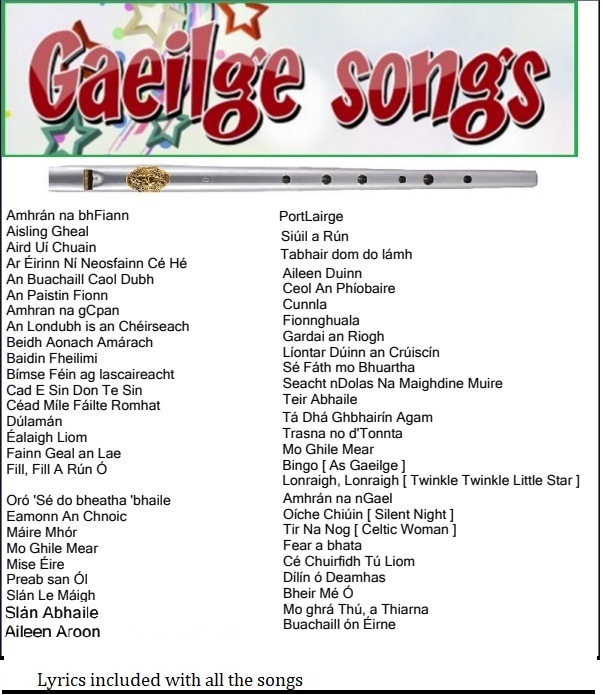

Below is the list of sheet music and tin whistle songs that are in my ebooks. This is the largest collection of tin whistle songs ever put together.[over 800 songs ] Including folk, pop and trad tunes plus German And French songs along with Christmas Carols.

All of the sheet music tabs have been made as easy to play as was possible.

The price of the ebooks is €7.50

All of the sheet music tabs have been made as easy to play as was possible.

The price of the ebooks is €7.50

1. (D)Seal da rabhas im' (Bm)mhaighdean (D)shéimh,

(G)'S anois im' (D)bhaintreach (G)chaite (A)thréith,

Mo (Bm)chéile ag (G)treabhadh na (Bm)dtonn go (D)tréan

De bharr na gcnoc is i (A)n-imi(D)gcéin.

Curfá:

(D)'Sé mo laoch, mo (Bm)Ghile (D)Mear,

(G)'Sé mo (D)Chaesar, (G)Ghile (A)Mear,

(Bm)Suan ná (G)séan ní (Bm)bhfuaireas (D)féin

Ó chuaigh i gcéin mo (A)Ghile (D)Mear.

2. (D)Bímse buan ar (A)buaidhirt gach (D)ló,

Ag caoi go cruaidh 's ag (Em)tuar na (A)ndeór

Mar (D)scaoileadh uaim an (A)buachaill (Bm)beó

'S ná (G)ríomhtar (D)tuairisc (G)uaidh, mo (A)bhrón.

Curfá

3. Ní (D)labhrann cuach go (A)suairc ar (D)nóin

Is níl guth gadhair i (Em)gcoillte (A)cnó,

Ná (D)maidin shamhraidh i (A)gcleanntaibh (Bm)ceoigh

Ó (G)d'imthigh (D)uaim an (G)buachaill (A)beó.

Curfá

4. (D)Marcach uasal (A)uaibhreach (D)óg,

Gas gan gruaim is (Em)suairce (A)snódh,

(D)Glac is luaimneach, (A)luath i (Bm)ngleo

Ag (G)teascadh an (D)tslua 's ag (G)tuargain (A)treon.

Curfá

5. (D)Seinntear stair ar (A)chlairsigh (D)cheoil

's líontair táinte (Em)cárt ar (A)bord

Le (D)hinntinn ard gan (A)chaim, gan (Bm)cheó

Chun (G)saoghal is (D)sláinte d' (G)fhagháil dom (A)leómhan.

Curfá

6. (D)Ghile mear 'sa (A)seal faoi (D)chumha,

's Eire go léir faoi (Em)chlócaibh (A)dubha;

(D)Suan ná séan ní (A)bhfuaireas (Bm)féin

Ó (G)luaidh i (D)gcéin mo (G)Ghile (A)Mear.

Curfá

Ó chuaigh i gcéin mo (A)Ghile (D)Mear

(G)'S anois im' (D)bhaintreach (G)chaite (A)thréith,

Mo (Bm)chéile ag (G)treabhadh na (Bm)dtonn go (D)tréan

De bharr na gcnoc is i (A)n-imi(D)gcéin.

Curfá:

(D)'Sé mo laoch, mo (Bm)Ghile (D)Mear,

(G)'Sé mo (D)Chaesar, (G)Ghile (A)Mear,

(Bm)Suan ná (G)séan ní (Bm)bhfuaireas (D)féin

Ó chuaigh i gcéin mo (A)Ghile (D)Mear.

2. (D)Bímse buan ar (A)buaidhirt gach (D)ló,

Ag caoi go cruaidh 's ag (Em)tuar na (A)ndeór

Mar (D)scaoileadh uaim an (A)buachaill (Bm)beó

'S ná (G)ríomhtar (D)tuairisc (G)uaidh, mo (A)bhrón.

Curfá

3. Ní (D)labhrann cuach go (A)suairc ar (D)nóin

Is níl guth gadhair i (Em)gcoillte (A)cnó,

Ná (D)maidin shamhraidh i (A)gcleanntaibh (Bm)ceoigh

Ó (G)d'imthigh (D)uaim an (G)buachaill (A)beó.

Curfá

4. (D)Marcach uasal (A)uaibhreach (D)óg,

Gas gan gruaim is (Em)suairce (A)snódh,

(D)Glac is luaimneach, (A)luath i (Bm)ngleo

Ag (G)teascadh an (D)tslua 's ag (G)tuargain (A)treon.

Curfá

5. (D)Seinntear stair ar (A)chlairsigh (D)cheoil

's líontair táinte (Em)cárt ar (A)bord

Le (D)hinntinn ard gan (A)chaim, gan (Bm)cheó

Chun (G)saoghal is (D)sláinte d' (G)fhagháil dom (A)leómhan.

Curfá

6. (D)Ghile mear 'sa (A)seal faoi (D)chumha,

's Eire go léir faoi (Em)chlócaibh (A)dubha;

(D)Suan ná séan ní (A)bhfuaireas (Bm)féin

Ó (G)luaidh i (D)gcéin mo (G)Ghile (A)Mear.

Curfá

Ó chuaigh i gcéin mo (A)Ghile (D)Mear

Irish / Gaeilge Ebook Of Songs For Tin Whistle. Price €6.90.

You'll be directed to the download page after payment.

You'll be directed to the download page after payment.

Mo ghile mear sheet music in D Major

Mo ghile mear tin whistle notes for the key of D

Mo Ghile Mear sheet music in the key of C Major

Below is a list of over 170 traditional tunes with mandolin / guitar chords in an ebook.

It cost €6.50

It cost €6.50