|

Gun Running For Roger Casement In 1916 is taken from the book by the German Captain of the ship that brought the rifles to Ireland in 1916 at the request of Roger Casement. The book was written by Captain Karl Spindler and the first two chapters are here Roger Casement Song Chapter 18 of gun running for casement this is a LibriVox recording all LibriVox recordings are in the public domain for more information or to volunteer please visit librivox.or gun running for keys mint by Carl Spindler translated by W Montgomery and eh McGrath Chapter 18 unwelcome guests the following interesting dialogue which was conducted in English now took place between the captain of the shatter and my meat where are you from no answer hello where are you from again no answer god damn I asked you where are you from duselman at last took the trouble to answer and showed it across and allowed voice good morning Helen Damnation shouted the English captain I don't want your stabilities I want to know where you come from then first of all would you mind telling me who you are answered the mate calmly I am the captain of this ship was the answer are you the captain of the out no I am the second officer where is your captain he is asleep well wake him at once the devil I will the old man would half kill me if I called him in the middle of the night answered dusselmen very well then all do it the Englishman roared and he went to shade rather in the face with anger what you want to get killed ask the voice from above no but I'm coming on board to knock the sleep out of your captain you will see how the captain of a ship in the service of his Britannia majesty does it I'd like to see you answer the laugh let's see you do it one by one nearly the whole of the crew of the shatter had come on Deck and we're now interested spectators while the captain with much Circumstance and newer his ship to within a couple of yards of ours the Deck of this little steamer away so far below me but I could no longer see the men's standing on it after a while I heard the English captain shouts how am I to get up the side the laconic answer came I suppose the captain of a ship in the service of his Britannic majesty will show us how it is done they're now came a long pause while they were doubtlessly wondering on the shatter how to scale the steep side of our ship without the aid of a ladder then I heard the Englishman call out this time in a particularly polite tone please let down the ladder certainly with the greatest pleasure to meet answered but I must first call The Crew they are all still asleep then he lumbered slowly down from the Bridge and went forward cursing to Rouse the man as he went I heard a voice below me say god damn is damn fellow is no fool a statement which I sirely endorsed the crew of the shatter had apparently forgotten they could support their demand with force of arms it was quite a long time before the second mate return from the forecast of along with a couple of the crew who to all Appearances it comes straight from their bunks then a ladder was let down and with much puffing and blowing the Englishman clamored up followed by a couple of his Men as they posted themselves right in front of my window I had to quickly pull the blind to cross now then where's your captive asked the Englishman and I heard the mate answer don't felt so loud man if you wake this skipper you will know about it he is the most fear captain in all Norway but it is most urgent that I speak to him so come along with me alright answer do so many but you will have to go first now you go in front answer the Englishman who began to think there was something uncanny about the business oh all right then that was all I heard for I quickly both of the door and made all ready for the reception while the pair were coming along the cabin passage knocking first circumspectly then harder and harder they tried to Rouse the captain of The Owl leaning my head back somewhat I answered a couple of times with a half audible curse then there was silence for a while all I could hear now was whispering voices and then the knocking began again this was more than I could stand I pulled off my vest in Thai put my hair and suitable disarray and went cursing loudly to the door in accordance with our plan I spoke load German on the assumption that the Englishmen would probably take it for Norwegian Damnation what's the meaning of this confounded drumming in the middle of the night I shouted in my deepest base while I open the door good morning sir I'm very sorry to have to trouble you so early in the morning with these words my English colleague greeted me at the same time he carefully took a step backwards in his left hand he held a rusty pistol which might well have dated from the time of Nelson with his right he touched his grease stain cap in a Kurt salute behind him stood beside my mate 6 English semen armed to the teeth and closed and rather fantastic and dirty uniforms I put on the sternest appearance I could possibly assume and then addressed him in brow beating tone in English if you wish to speak to me be good enough to wait until I have dressed as I spoke I slam the door in his face all this happens so quickly that the Englishman did not know where he was there was quite a long pause before I heard him say to the mate are all your Norwegian captains such boundaries and do some in replied all I can tell you is that this one is a regular tartar that he invited him to take a seat to the mess room which the Englishmen very willingly did I now knew enough to be able to play my role in this comedy the popping of a court next door told me that duselman had already started the good work for nearly a quarter of an hour I pounded up and down the room splashed in the wash basin and joyfully anticipated the scene that was now coming men of this description could be managed without bloodshed there was no doubt about that my soul anxiety was less these fellows while they were still sober would go smelling around the holes but my man had cleverly understood the situation and had invited the crew of the shadow to have a little drink in the forecastle so that for the present there was nothing to fear from them I opened why the risky Locker under my bunk so that anyone sitting on the sofa I could easily see the bottles of whiskey and brandy standing and shared racks and then showed it into the mess that I was ready for the interview the man with the whiskey nose appeared immediately and took the seat I offered him on the sofa it was only now that I saw to my horror that my uniform jacket sword belt and cutlass we're hanging beside the wash stand I promptly through the towel which I still held in my hand over them and had the satisfaction of noting but the Englishman had spotted nothing during the conversation which ensued I was at first very surely and Kurt when the usual questions where was I from and where was I bound for had been disposed of the Englishman asked me what my object was in anchoring here I told them my engines not that you will see very much I remarked by the way everything is so higgly piggly down there at the same time I placed a small ladder for him and with the gesture invited him to go down was he afraid that the ladder would not carry his weight or did he think to the scent would be too unpleasant anyway he waved the latter aside and said Curtly alright then without another look at the inside of the whole he related to me how he had weathered this awful storm here in trilly Bay what a terrible time he had had and how by his clever handling he had preserved shattered too from destruction so excited did he get over his account that he did not notice that I had shepherded him back to the door of the cabin thank goodness at any rate I had now got him away from the Dangerous number one hold which of course was still wide open in order to cut the business shorts by now asked him if you'd like to see my papers as he answered in the affirmative I pushed him into the cabin and the next moment he was again seated on the sofa with me opposite him then I offered him a fat Havana in order to bring two cups of coffee this of course was all by play for an Englishman like this would certainly not drink coffee first thing in the morning so he turned away quite angrily red Bruins put down a large cup of coffee under his nose to my joy I noticed that the whiskey cupboard had not escaped his attention he stared and stared between my legs the locker so I remarked quite casually perhaps he would rather have a little whiskey he did that with an energetic you're the man for me he slapped me on the shoulder and with characteristic shamelessness started to go to the locker himself and pick out the best White Horse I let him go ahead and in the meantime fetched a big Tumblr so that his ration would not be too small then I held out the water bottle and asked how much but the Englishman waved aside declaring no water you know we never see this stuff here what better could I have wished the conversation now became fairly lively and when the Englishmen asked to see the ships papers I very willingly got out my whole collection of smoke black and documents he pawed them over repeatedly but I noticed that first glance that he had no earthly idea of the meaning of the documents he handed me a book design I wrote myself down in several places is kneels Larson captain of the Norwegian steamer out with pit props and Peace goods for Christiana for Cardiff and giona at the mention of Pit props he remarked cheerfully that this cargo was badly wanted in England and in confirmation of this statement the emptied his glass at a gulp without buyer leave he at once poured himself out another glass and assured me again and again the coffee which I drank was very bad for the nerves referring to the Norwegian newspapers lying in front of us which were now three weeks old I asked him if he could let me have a few English papers as I was anxious to know the latest war news he got up at once went up on Deck and going over to the side shut it an order to the man on his ship to send over immediately all the papers lying in his cabin the conversation now turned on the events of the war with the result that I found myself in a peculiar position of having to join with one of my deadly enemies in cursing my beloved Germany which nearly broke my heart I would have preferred to have knocked the fellow down for some of the ridiculous statements he made but in view of what I hope to obtain from him I had to swallow it all and chime in with him in the meantime my second mate had joined us a company by one of the English Petty officers we carried a huge parcel of the latest papers under his arm I now went back into the cabin with the Petty Officer offered him a whiskey and cast my eye rapidly over the papers chance decreed that a paragraph in the second paper I took up caught my eye it stated that on Wednesday ie two days before our arrival by order of the English officer,nding district several shinn Fain leaders had been arrested Infinite on suspicion of being concerned in a conspiracy against the English government so this was the answer to the riddle and the paper stated that an Irish pilot whose name I have forgotten had been arrested on a similar charge that could be no doubt about it it must have been our pilot the man for whom we had been waiting so anxiously here it was no easy task for me to conceal from the Petty Officer the difficulty I had and following his remarks on all sorts of unimportant subjects fortunately the other two now reappeared and I was able to switch off I had the papers to do some in holding my thumb on the paragraph in question so that he noticed it at once at the same moment the English captain clapped me on the back and said in a reassuring tone captain you need no fear of you boats I'll keep a lookout for you as I did not at once grass the meaning of these words he added an explanation you're me told me you were very much afraid of the u-boats turn from this voyage of course I can understand this in the case of a man who's engaged to a girl and Christiana and is to be married in two months time but don't worry so long as you're compelled to remain here for repairs I will lie at the entrance of the Bay and take care that no U-boat and now in return for that give me another drink soothing the action to the word you poured out drinks for himself and the Petty Officer I'm afraid my face did not give the impression of much intelligence at this moment not that I had not understood the words but I feared that ducealmen by his well intended me more harm than good if the Englishman really should keep a lookout he might possibly succeed in syncing our submarine which might still appear at any moment the more I attempted by all sorts of objectives to dissuade him of His purpose the more obstinately he clunged to this plan out of gratitude as he said then he swallowed his class of whiskey in one gulp with big tiers rolling down his modelling face it if now appeared to me imperative that I should have a few minutes undisturbed conversation with duesome men so I summoned the first mate and asked him to look after my guests making the excuse that I just wanted to have a look around to see that all was well I left the cabin which was now almost unbearable for tobacco smoke and the smell of whiskey dooman followed me at once we debated what we should do with the fellows it would have been a simple matter to overpower them and tie them up for I now learn that the English who were sitting in the forecast so with my crew were dead drunk I'm not the same was probably true of the Men Who remained on the shatter for ducealmen had had the inspiration to present four bottles of risky to the boat Screw but the execution of this plan would not have helped us we had no manner of use for the steamer and we could not sink her without exciting suspicion now too when we knew that arrest had already been made and truly and that the district was probably under martial law it would be useless if we man the shadow ourselves and ran it to reconoid her and try to get in touch with the ship veiners this would cost me at least four men and I should probably never see them again we were too much under the observation of the various signaling stations to dismount the shatter's guns and take them over and there was no other Anchorage in the neighborhood where we can do it we therefore came to the conclusion the best thing to do was to make the fellows dead drunk and then let them go we dare not stay here later than the next morning if by that time nothing had happened I intended to try and break through into the Atlantic and start commerce rating in any case I intended during the coming night to send a boat to shore even at the risk of being discovered by this time things were getting lively in my cabin the huge quantity of whiskey they had consumed was evoking various discords apparently intended to represent it's a long way to taperary and coming from the forecastle also singing a rather damageable boring could be heard well let them enjoy themselves we decided we would sound them thoroughly and then get rid of them as quickly as possible when I re-entered the worthy captain held out to me photograph which he had taken from the wall asking if this was my fiance from Christiana I laughed and said it was it was a picture of my sister holding her youngest hopeful in her arms however I had the satisfaction of knowing that the Englishmen were quite convinced of our Nora region nationality they had no got to Brandy I noticed if they continue to mix their drinks in this fashion they would assuredly dive alcohol poisoning the captain although speech had become a matter of some difficulty to him was getting more and more loquacious between his hiccups he told us that he was on outpost Duty here but that he had made himself quite comfortable all the same two hours before dark at the very latest he always preceded to acquired Anchorage behind Kerry ahead in order to be able to sleep and comfort his crew 2 he added were all in favor of a good night sleep the only privation they suffered was lack of whiskey this being strictly prohibited on British warships that he said was the reason why he was so glad to see this opportunity and to find so kinda host I'm not a benevolently and asked him how long he had been stationed here not very long he replied I was sent here a couple of weeks ago from Aberdeen mainly in order to intercept the German steamer which is expected to arrive here at any moment we of the out involuntarily glanced each other the business was getting more and more interesting every moment when I'd recovered from my first astonishment I asked a few questions yes I suppose you think the Germans don't break through the blockades of the captain when I assure you they do look at the move for example she got back all right and in order to wash out the impression which the return of the movie made on his English sailor's heart he hastily took a big drink the whiskey trickling down from the corners of his mouth then he went on again look here I will tell you how it is you norwegians are good fellows so there is no harm in my telling you although it is really supposed to remain absolutely secret well we the best to say the naval staff have discovered that these damn swine the Germans want to join the Irish in bringing about a revolution that is why they chose me in order to capture the auxiliary Cruiser which is to come in here and bring arms for the Irish look at the harbor and the entire Bay the whole place is bristling with guns would a fine reception the Germans will get from us of course the beggars are clever but we English are a jolly site clever I could no longer contain myself I pursed out laughing and the first and second mate joined in this kept all that we had experienced so far fortunately the Englishman thought we were laughing at the stupidity of the Germans for he repeated again and again yes there are terribly stupid in spite of all their cunning I now knew all I wanted to know I rushed to the locker and telling this splendid clever Englishman but I wished him the very best of luck on his quest I got out another half dozen bottles of whiskey and a box of cigars which I presented to him that is brave crew as a token Of My respect he himself was incapable of carrying the Bottas so we stuffed them in his pockets and those of his Petty Officer telling the gentleman that we must now get to work and must beg them to leave the ship and they with loving look at their presence declared their readiness to go as he was getting up the captain beckon to me and with his hand to my ear hiccuped If by any chance you catch sight of the German Cruiser out there be careful that she does not sink you and form a signaling station at once or one of our many cruisers which are waiting in the offing for her you will be well rewarded by the government I tell you that as a friend I laughed and promised to do so and then pushed the two of them out I stood upon no ceremony in dismissing the horribly drunken pair the rest I left to my crew and in about 10 minutes do so many was able to report to me that all the English dead drunk had left the ship and that shatter too was steering as zigzag course for the mouth of the Bay later we found out that he kept his word and kept watch for us Against submarines in a distance of 5 miles poor unsuspecting fool the first thing I did then was to sit down in the cabin in order to regain my breath cool down and collect my thoughts we had entertain for two solid hours if I've been told that in six weeks the world would come to an end I might have believed it but if any man had told me that in my own cabin the captain of an English outpost boat would warn me against myself I should have thought him mad what we had just gone through was so incredibly funny that I might have thought it a dream if the statement of the shatter captain had not reminded us of the seriousness of our position and very serious it was all hope of landing or communicating with the shin thiners had now disappeared there was treachery about danger on all sides whichever way I looked we had chanced into a wasp nest and could count ourselves lucky if we got out again in the next 24 hours I summon the whole crew to the upper deck and outline my scheme in order at any rate to save my valuable cargo I proposed to leave the bay immediately after dark and try if I could get out 30 miles into the Atlantic before the moon rose trusting in the lock that had till now accompanied us I was quite confident we should succeed in escaping once we were out in the high seas the future could take care of itself I had before my mind the possibility of selling our cargo in Spain which was only a day and a half sale distance or perhaps in Mexico if we could get there to leave the bay at this moment would have been a blunder for it could not be suppose that all the English were such silly fools as our friends on the shatter the signaling stations round us had witnessed the visit from the shatter in the morning but they would most certainly have been suspicious if we were now suddenly to up anchor and Away for they were not going to believe that we had run in in order to enjoy the scenery in truly babe by night also they would undoubtedly have noticed that we had not yet been really inside the harbor if they should ask the shatter why we were remaining here the explanation would be that we had trouble with the engines which would cause much less suspicion than suddenly clearing out and saying goodbye to truly we all agreed on this and therefore decide to remain if possible until night fall if some Stout shin-fainers he would certainly make every effort to give us a sign if nothing more as a precautionary measure I had the munitions covered up with ropes another rubbish and then had the hatches closed you can never tell then the chief engineer rushed and is crew got to work and thoroughly overhauled the engines and preparations for a run all out while this was being done before noon past without any other event of interest and of chapter 18 Red by Paul Parkinson Calgary Alberta March 2023 chapter 19 of gun running for casement this is a libraox recording only revok's recordings are in the public domain for more information or to volunteer please visit librivox.or gun running for casement by Carl Spindler translated by W Montgomery in eh McGrath a stern Chase shortly after 1:00 p.m. Small steamer beyond Carey head on the north side of the Shannon the foam in Her Bows told us that she was travelling at high speed as she was holding a Westerly course I had at first no suspicions she was still so far off that even with our prismatic glasses that could make out nothing I therefore got the big glass which is already stood me in good States so many times and perceived to my astonishment that the steamer had a long gun completely uncovered mounted on a forecastle deck her tall Top Mess showed that she had a wireless installation another Patrol built in at this time a much bigger and more modern one than our friend the shedder I handed my class to the mate so that he could see for himself he has scarcely focused on the boat when he hastily exclaimed she's altering course she's coming straight for us I could see now with the naked eye that this was a fact the place was getting unhealthy for us and we needed no time for deliberational for our next move all hands on dick Step by to way anchor have seam up for four speed all hands were at this station is in a moment kepsen creaked and grown in every joint bump bump all I wants it stopped the Anchor had evidently got wedged between the rocks I felt as if I were standing on hot coals that actually put the Telegraph forward in order to simply part the cable or to slip it when the caps started to turn again as soon as ever the anchored was free we started of course due West and high time it was for the stranger was physically drawing near we just a distance to be at most nine miles so long as she did not catch us up we were all right where we were still a neutral steamer so far as she was concerned i'd worked out in my head what it happened Lupe had presumably won the naval base in Limerick about us in the Admiral and,nd there probably not trusting too much to his shedder too it sent out a bigger boat to trolley to have a closer look at the suspicious Norwegian a high English officer assured me later that my guess was practically correct a plotillo flag at a mass hit and the fact that she altered course to southwest as soon as we started confirm my conjecture our unmistakable intention therefore was to cut us off it was now more than ever a question of legging it we can no more risk a second examination and we could risk an exchange of shells in which we with our old Russian rifles and homemade guns was certainly have come off second best in order to get full steam quickly I ordered all hands to the so-called out quite close to the coast for the Rocky Shore is here so steep that one can approach with safety within 40 yards the dense clouds have smoke from our Funnel swept along the Rocky wall and world into the Deep fishers as if drawn into an air shaft the English vote was coming dangerous laid near the question now was which of us had the longest legs we reckon that she was doing 12 knots or we on former occasions had never done more than 11 it was therefore to be expected that she would slowly but surely catches that was to be avoided at any cost in order to further encourage them in the so-called call down to them from time to time through The Voice pipe the distance between us they work like horses and after some time I was able to state that we were keeping our lead why the English vote did not at least send a shot across our vows is still a mystery to me especially when she found that we took no notice whatever of her constant signals in the meantime we had approached our old friend to shatter which was leisurely wallowing up and down just under the battery at about 500 yards from the shore she seemed to have noticed us at last Force she turned slowly and steamed towards us I therefore called the second meet up on the bridge telling him to keep his eye on the shatter and gave the wheel to abstral we gradually come so near that without the glasses we can now perceive The Guns of the battery trained on us a lively exchange of Signals was taking place between the battery in our pursuer and then a signal was forceded on the shadow also unfortunately it was impossible to read it for there was not a breath of wind the devil had the Rascal been deceiving us and was the drunkenness all play acting in order to be able to attack us in front and conjunction with the battery while the other boat attacked us behind for one moment I was in client to fear some strategy Fred appeared impossible that the shatter signal could mean anything but stop at once as a precautionary measure I therefore ordered all preparations for blowing up the ship at the same time I gave the order to starboard the helm in order to ran the shatter for I was determined that if we went down we should take her with us the next few seconds must decide our fate we were going straight for the shatter at full speed but she made no effort to escape being around what could be the explanation against steadily through the glasses suddenly the shattered turned to port and as she healed over for an instant on account of the sudden turn we read the signal we could not believe our eyes from the signal Howards of the shattered the signal so well in the old days TDL on boyage I rushed to the hill toward the wheel around to port and anxiously counted a second until they all began to answer them fortunately the high speed of which find me the weather effective but only just in time all our lives hung on the fraction of a second in a very next second we shall pass the English vote not a ship's length off all of this of course happened in much less time than it takes to tell it but the greatest surprise of all was still reserve for us the brave captain was standing on this little Bridge holding on like grim deaths in the real his crew stood or rather large step out on the deck at the moment when we ran pastor at full speed he tore his hat off waved it around his head yelling like a red Indian and called for it three cheers for the out to which his crew bald and enthusiastic response if at this moment had a couple of models of whiskey by me on the bridge I would have willingly thrown them to the crew of the shatter out of gratitude for the Salvation for there can be no doubt that conduct of the shadow crew at the very least made the battery officer uncertain of his ground I heard later that the battery in response to a signal from our pursuer was just about the fire at us while we were standing away from it that did not do so because the cheers of the shadow Crews seemed to indicate that we've been to victims of some mistake of course we answered the greeting of the shatter with kept waving and a friendly goodbye do someone in fact ran up the signal xor thank you to cap it all I dip my flag as we left the most friendly Englishman I've ever met on the Seas none of us I'm certain well ever forget this moment it was not till afterwards that I heard from the crew that our lives hung once more into balance one of the crew and mistaken my order to dip the flag and was under the impression that I'd said tisk which was our pre-arranged blowing up the ship he was just about to break out the German naval encin that discern and the chief offices stood ready with the fuse when the mistake was realized so this little intract went half all right it any raised so far as we were concerned not for the captain of the shadow however for heard some months later that the English Admiralty considered his conduct two gentleman like and deprived him of his commission after a court martial its innocent to imprisonment the battery now lay a good mile a stern but we were still within range of his guns and are pursuer was close on our heels we therefore had to make every effort to increase the distance which was of course largely question of correct steering so the first may took over the wheel while the second made work the engine room Telegraph down below my brief soakers half naked sweat literally pouring down toiled at the glowing furnaces while The Others untiringly fetch baskets of coal from the bunkers engineered a stood at their stations in the engine room ready each moment to carry out the orders as it came from the bridge we were steaming with every ounce of pressure we could get meanwhile the English voted drawn there the second made it once shot it down to two get a more steam Englishmen will be alongside in no time and with the sinister smile he added if you fellows can't make more steam say the word diffuses ready but in that case please label your bones the noise of shuffleds the banging of furnace stores and allow cheer where the answer that came up from the engine room chief engineer came puffing up the ladder and chatter to me captain if we go on like this the boilers were burst the same as little pass the red mark I thought it was long ago but it's no good worrying about that my dear fellow we must break through it all costs as it is we are still got a chance but if this fellow storm of a succeeds and catchiness we can make our Wills you shook his head seriously then he plunged down into his own domain below and encouraged his men to work as if the devil were at our heels by now the wireless voted come up with a shatter which was still making leisurely for trolley to our Joy we noticed they have the vessel carefully maneuvering in order to come alongside the shadow this gave us a good start and we can see you several people jump from the wireless boat which was letting off a white cloud of hissing steam onboard The shatter what happened then was not hard to guess but the captain of the shedder was certainly not reveal it as long as he lives unfortunately we were unable to watch the proceedings from close range after an interval of about 5 minutes the shadow went about him and then both boats took up The Chase but our pursuers had lost so much time in laying their ship alongside the shatter that they had little chance of overtaking us for our brave little out was now according to the pattern log doing more than 13 knots across line now been around towards Southwest and as we were still keeping the same distance from it we were soon out of sight of the battery keeping the same speed we ran for another hour and a half and noted with joy that our pursuers were visibly dropping behind the English also soon saw the impossibility of overtaking us for they suddenly turned off the port and seems slowly towards the coast where they soon disappeared in one of the many bays it was getting on for half S3 so he must already put some miles behind us an engine room staff heard that our consumers have given up The Chase they greeted the news with three rousing cheers we all gave a sigh of relief especially in the chief engineer who lost no time now and letting the steam down below the red danger mark on the pressure gauge we were now getting near the mouth of the Bay see what studied all over with little islands and rocks some of which protected only a couple of feet out of the water one of the larger islands around our interest at the foot of the massive Rocky Walt there was a semicircular opening of natural formation so big that a sailing boat could comfortably go through to the Far Side unfortunately the chart showed so many Shallows between these islands that I felt bound under the circumstances to take the longer course around the outlying islands a proceeding which at any rate gave me more freedom of movement and that at the moment was more important than ever for it was inconceivable that the captain of the wireless vote after giving up the hopeless chase would sit down into nothing so we were not particularly pleased when we noticed the Lighthouse with signaling station and wireless installation facing to see on Dunmore Island the last island on the south of the Bay without doubt these people already knew all about our flight fortunately for us however they were on armed so that we had to reckon only with the fact that they would watch us and Report every alteration of our course to the nearest coast guard stations and ships the Atlantic now late before us and I had the choice of Steering North West or South South the. to me to suspicion the English had so far had no positive proof against us the Norwegian flag still flew at our Stern and as I told the captain of the shatter that we were bound for Cardiff and infrared Italy I thought it was best to keep up appearances while it was still daylight and to steer a southernly course if a worship should then come along we should be able to justify our correspa means of our manifest then when it got dark I intended to turn westwards in order to get away from the patrolled coastal area and of chapter 19 chapter 20 of gun running for casement this is a liberox recording only provokes recordings and public domain for more information or to volunteer please visit librivox.or running for casement but coral Spindler translated by W Montgomery and age McGrath the phantom ship in a trap at the mouth of trolley Bay we met a stiff north wind and here and there at the waves were topped with bone a couple of small steamers deeply Laden were crawling along Northwards hugging the coast where they were too much afraid of the German submarines the venture out on the open sea the second one was a Norwegian like ourselves the name was unaccount of the distance unreadable but then the shape of the vessel was devilishly like that of the out I wonder if this was the real loud which was due back from the Mediterranean just about this time it would have been a nice friend Connor for us unfortunately I was unable even afterwards sasseting effects the only information about our double that reached me was a newspaper article some months later stated that the Norwegian steamer out from Bergen had been torped in sunk on the second of October of the same year favored by winning current we were now steaming at a good speed into the Atlantic slowly but surely turning away from the coast so as to raise no suspicion shall we succeed I would really have preferred to see the sky overcast and a good has seed running that would have been the best protection against the English Patrol ships it was however now and afterwards most beautiful clearer weather not a whisp of smoke was visible on the horizon we had still nearly four hours of daylight in front of us I need not till how anxiously we all waited for the sun to go down in few of our successful flight from trolley the crew were already busy with plans for the future they thought we could now start at once on our war with the dummy guns it was so pleased with the imminent prospect of Commerce rating that they saying all sorts of lively songs studio company Lenovo concertina and in order to avoid spoiling I did not let them notice how little Enthusiasm I have for counselors of this sort s towards 6pm of smoke cloud was noticed in the southwest which grew larger every moment and rapidly came near soon afterwards we noticed the second smoke cloud it came so close after the first it was evidently from the same vessel so we had a two funnels steamer ahead of us in the message came into the wireless mess and the spotting top it could be no doubt about it she was an English version we estimated that she was doing at least 20 knots if we now try to run away in our tram seamer speed she would catch us in an hour if she did not Honor us before them with the show so carry on only cool hits could help us know together with a fair amount of impedance worship was traveling at top speed it was not long before her upper works and in the whole of her home came into view it was an auxiliary Cruiser one of the fast channel steamers which in peacetime plied between England and friends this time we were of course had Action Stations on board the out and it's the say all preparations have been made for blowing up to ship a suspicious material was all packed away in the Magic Box the engines were at half speed now myself was marching dead slow up and down the bridge we were once more the old tramp group of a few days before the Cruiser was no doubt one of those which had been warned some areas previously by the wireless ship what we had to expect this time was at the very least a thorough examination of the vessel and even if we came successfully through this we should probably be escorted in the nearest port where the suspicious out would be unloaded in our cargo of munitions revealed now follow some minutes of 10 sex expectation only half a mile separated us from the Cruiser our Armament consisting of several 4.5 number of machine guns was clearly visible we expected she would come with inhaling business but she did not instead of that she steamed alongside us in his exact course for about 10 minutes signal we were expecting never came nearly her whole Crews stood on dick easing at us with curiosity we went ahead as if it were no concern about us but who can describe our astonishment when the English ship is if she had seen all she wanted to see turn sharply East and steamed off as she had come at top speed now what did this mean we had no idea that time that it was the fear of our imaginary heavy guns are torpedoes and the submarines that were escorting us it kept the cruiserator distance and had Center off post ace for reinforcements unfortunately these were not long incoming up the sun was now low down in the west through such a dazzling glare on the water it was actually painful to scan the Horizon in doing so we soon made the unpleasant Discovery at our cruise there was not the only shipment view almost ahead a little on the Starboard valve another English ship was giving up and to start board yes what the devil was at ahead a Stern in fact all round which is was soon evident came from other Monsters similar to the first all auxiliary cruisers and all at the same type all the steamers of the channel service seem to have been concentrated against this footnote a few days later I learned through an English naval officer that the wireless boat went off. Are you just have to wait anchor sent an urgent wireless message to passenate edmullen,nder horse warm if auxiliary cruises and Destroyer sicknesses about 30 vessels altogether these boats by virtue of the great speed were in a very short time able to form a coordinate from fastnet to beyond the northern outlet from trolley Bay so that we should have been cut in any case no matter what course we had taken in footnote there was known necessity for deliberation we were hammed in all round and there was no way out all these ships armed with guns and machine guns against our little out who sold Armament consisted of a couple of wooden cannon and still these fellows appear to be horribly afraid of us but he still kept their distance zigzagging around this it showed that they expected at any moment a Shell or a torpedo I really had to laugh at these heroes of the sea as nobody had yet borrowed our way we kept on our course at the same speed something is found to happen said I to myself but this can hardly be intended as a guard of honor and something did happen at last shortly after seven o'clock the Cruiser which we at first sighted him so close that we could easily read her name Bluebell at the same time you ran up a signal stop at once the other ships kept at a respectful distance the guns clear Direction we were prepared for all eventualities on the forecastle head the ships dog was barking as if men his Instinct told him that he had to play his role very carefully as soon as I stopped the ship other signals followed but ship is that where are you from where are you bound for I could not now give Cardiff as my immediate destination as we gone too far off the course so in order to give a credible answer I replied Genoa and Naples for in case of necessity we still had on board a number of doors and window frames bearing this address I had retained them at the time with a view to building a deck house in order to alter our appearance of necessary in hoisting the signal one of my proof intentionally broke the signal how you this was a brilliant idea for every moment to leave might be important even if no you both came to our help The Darkness which was rapidly falling might save us a tramp steamer like the out could not be expected to have spare signals and order to convince English if I willingness however we hung out one after the other from the Bridge the flags the composed the message and Discover some fashion we signal backwards and forwards for about a quarter of an hour then came along pause during which the searchlights on the blue bill were used in order to communicate with the other ships the continual crackling from our aerials proved also that wireless was being used other ships head in the meantime come on the scene and the,nder here to be on board one of them for the signals from all the ships were now directed to this particular Cruiser all of a sudden the Blue Bell signal to us proceed we were prepared for anything except that we should be let go Scott free we did not wait to be told twice in a few moments the odd was again underway in order to conclude the affair in the approved manner I ordered the first maid to dip our flag slowly in respectfully which visibly impressed the English for they returned us salute most courteously it really appeared as if these English folk were convinced that we actually were the Norwegian out as we had stated all the same I did not feel too easy in my mind as we seemed away I could not persuade myself that we had bluff this lot also especially as they had not only been warned but actually been sent to intercept this as was clear from the catechism we had just gone through when we had gone some distance I therefore ordered to speak to be gradually increased that if we should get away as quickly as possible from the Enemy we did not need to worry very long we had already put a considerable distance between us cruisers had stopped and not lay like a swarm of locus and one spot apparently holding a council of War eight bills had just been struck when there was a Commotion of Us swarm suddenly turns out and came racing after us like a peck of Hounds at the mass of the leading vessel flew The Familiar signal stop at once for the second time I stopped the engines and waited events while unfortunately no other course was open to us if we had not stopped it would have set about us at once I waited for perhaps five minutes and has nothing else happened in that time beyond the fact that the enemy had come considerably near I got a bit impatient and signaled why instinctive answering our signal all friend the Bluebell steamed to within 150 yards of Us stopped and prepare to lower the cutter to officers and about 12 Siemens all armed to the teeth had taken their places in it so here was the price crew at last a load fell from all our hearts but there was an excellent prospect that we might escape during the night while fascinating Queenstown waited for us in Vain when I shouted down to today look out price through coming the make grind all over his face and other screen with him for now as they said it was a chance of doing something at last during this time the chief engineer was busy forward repairing the seam winch and in order to see if it was working and he laid it run for a moment it may have been because of this noise or because the English mistook some empty tin or other floating object for a periscope at any rate immediately the wind started we heard shots all round using gold with the ringing of engine room telegraphs and the next moment the whole flotilla scattered as if struck by lightning put the English paper stated later on the authority of authentic reports that the captain of the Bluebell on account of The Heavy Seas was unfortunately unable to launch a boat and send a price grew on board the out I wish to stayed in frederically in contradiction that there was neither when norsee at the time and put once more we were all alone on the sea this was a cat and mouse game with a Vengeance in order to put an end to the business I now signaled may I proceed answer was wait all the cruises slowly approached again I signaled please inform me why this time there was a long pause before the reblacking and a very unpleasant reply and was follow me to Queenstown horse South 63 degrees East person he got suspicious our fate was now decided with a price grown board which would have been dealt with according to plan we might have gained a high seas during the night but with an escort of arm fest steamers this was out of the question even in thick frog in the darkness of night it is very doubtful if we could have broken away from our escort now as in the case of all the other signals I answer First with don't understand for my only aim now was the game time to try to get them to put a price crew on board and that case an escort would have been unnecessary the Cruiser really made every effort to make his signal intelligible but the more trouble he took a less understanding we showed we seemed to have lost every shred of intelligence on board the out in Justice to them I must confess that the crew of the blue whale did their best to help us they tug like mad at the signals and altered course over and over again in order to let their flags blow out in the Wind but all in Vain nothing could make this understand what they want it the English did not appear to notice that we were fooling them or greatly daring the most short-sight it could but I only shook my head all the signal book I lost and pointed to it with my finger indicate that this signal was not given in our book then the Blue Bell plucked up courage and approached very very carefully to within 50 yards of us while this ridiculous exchange of Signals was going on it gradually became dark so that it really was difficult now to read the signals the Bluebell notices where we now saw a man with a huge megaphone preparing to shout something to us from the bridge in order to forestall him I shouted down a ladder for your price through instead of answering my question the Bluebell Sheard off about 40 yards from us their officers showed us by all sorts of pantomime that they had no intention of sending a boat I very friendly invitation had failed if we had only known what a mysterious ship we were supposed to be the arnelment and you vote escort that we were credited with many things would have been more intelligible to us as I wrote today the English papers of those days a come upon the most incredible reports in regard to our little out the mystery ship The Flying Dutch and other scare headlines followed by the most fantastic accounts prove what excitement they out costing England and above all among the vessels of the coast Patrol the other cruises it meanwhile formed a ring round us on some of the guns were manned and ready to fire at us at the slightest hostile move on our part we should have been riddled by the sea aboard the Bluebell at the menu tip lieutenant was known thrown on the signaling Bridge with that gigantic megaphone through which he continued to shout follow me to Queenstown South 63 East this was repeated time after time but always with the same negative result this Force might have gone on all night and I was beginning to get tired of it and the English captain also appeared to be losing patients where I saw him signed to the speaker to come down then we heard a few Kurt orders the Cruiser passes on the port side the next moment there was a flash and a show from the blue whales forward gun burst in front of our bowels as we were directly in his line of fire we were all stupid Fight For A Moment I had the violence of the concussion in plain English this meant the farce is finished Perth as we were not very anxious for anymore shelves the next would most certainly go not across our battle but into it I shot it loud enough for the English to hear all speed I hit South 63 East at the same time a sent a message to the chief engineer that I would hang you from the yard on if this full speed rows above five knots we recognize out that this speed we should reach Queenstown at 10 o'clock next morning it was nothing left for us but to follow the Cruiser further resistance would have been useless we therefore wall of belong at a speed of 5 knots behind the Bluebell which now to believe while the other ships spread out all-round us magnificent escort for us 22 men the wind shifted to North northwest and then died down while the few clouds which were still in the sky disappeared with them the superior are Last Hope of Escape the Bluebell s was to be expected was not very pleased with our speed with all her protests made by means of a signaling lamp did not help a bit but more his signals flashed the slower we became the conversation was very funny but instead of using the electric Morse slam we used the small paraffin making the dots and dashes by holding a hand in front this was of course an extremely cumbersome method the ever-increasing the English muslimentally more than a dozen times they signaled faster which I replied at first don't understand afterwards I answered currently impossible why demanded the Bluebell engines broken down then a long pause they were most probably debating how they might compel us to increase our speed after some time we were informed if you don't get a full speed of once I will make you this did not sound very friendly not worry much press it to myself that after all the anxiety which the enemy had shown to get us to the nearest sport they were not likely to fire at us the Mostly would do would be to send a price grew on board which was exactly what I wanted then even if the ships were mean by us it watchfulness would be certain to relax so instead of answering the thread I replied come and see for yourself this was a piece of impedance but it was just possible it might prove our Salvation to my chagrin however the English showed no desire to accept my invitation they resigned themselves to their faith and we had very few more signals our pace now became a crawl with the patients of sheep they steamed along zigzagging now to the left now to the right evidently afraid we might discharge it torpedo at him at any moment the various orders for altering course had ought to be repeated about 10 times before we pretend to understand and the Blue Bell took it all without further protests and chapter 20

0 Comments

The first version of the song is in the same key Jack Keogh sings the song in.

[F]It's hard to be the country song by a good [Bb]old country band And hear [F]all of the music from the singers in this [C]land There are [F]songs of love and heartache and [Bb]some true stories [C]too And [F]songs to lift your spirits when [C]you are feeling [F]blue [Bb]Singing country music since [F]I was about me time I followed all the country bands and I danced in every [C]hall My [F]head full of ambition to re[Bb]cord a song or [F]two I'm glad to get the chance for to [C]sing my songs for [F]you [F]Dreams of being a country star since [Bb]I was only small [F]Singing to my heart's content, and learning from them [C]all I'm [F]waiting for the day each [Bb]band to roll into [C]town And [F]everyone would gather to [C]hear that country [F]sound Singing country music since I was about me time I followed all the country bands, and I danced in every hall My head full of ambition to record a song or two I'm glad to get the chance for to sing my songs for you I hope I will be playing with a band on my own someday And I get the chance to meet you all on my journey along the way For singing country music means everything to me And it's great to feel the welcome from this country family Singing country music since I was about me time I followed all the country bands, and I danced in every hall With my head full of ambition to record a song or two I'm glad to get the chance for to sing my songs for you Singing country music since I was about me time I followed all the country bands, and I danced in every hall With my head full of ambition to record a song or two I'm glad to get the chance for to sing my songs for you Now I'm glad to get the chance for to sing my songs for you Guitar chords in the key of G G]It's hard to be the country song by a good [C]old country band And hear [G]all of the music from the singers in this [D]land There are [G]songs of love and heartache and [C]some true stories [D]too And [G]songs to lift your spirits when [D]you are feeling [G]blue [C]Singing country music since [G]I was about me time I followed all the country bands and I danced in every [D]hall My [G]head full of ambition to re[C]cord a song or [G]two I'm glad to get the chance for to [D]sing my songs for [G]you [G]Dreams of being a country star since [C]I was only small [G]Singing to my heart's content, and learning from them [D]all I'm [G]waiting for the day each [C]band to roll into [D]town And [G]everyone would gather to [D]hear that country [G]sound

Guitar chords in the key of G

G]It's hard to be the country song by a good [C]old country band And hear [G]all of the music from the singers in this [D]land There are [G]songs of love and heartache and [C]some true stories [D]too And [G]songs to lift your spirits when [D]you are feeling [G]blue [C]Singing country music since [G]I was about me time I followed all the country bands and I danced in every [D]hall My [G]head full of ambition to re[C]cord a song or [G]two I'm glad to get the chance for to [D]sing my songs for [G]you [G]Dreams of being a country star since [C]I was only small [G]Singing to my heart's content, and learning from them [D]all I'm [G]waiting for the day each [C]band to roll into [D]town And [G]everyone would gather to [D]hear that country [G]sound Key of D [D]It's hard to be the country song by a good [G]old country band And hear [D]all of the music from the singers in this [A]land There are [D]songs of love and heartache and [G]some true stories [A]too And [D]songs to lift your spirits when [A]you are feeling [D]blue [G]Singing country music since [D]I was about me time I followed all the country bands and I danced in every [A]hall My [D]head full of ambition to re[G]cord a song or [D]two I'm glad to get the chance for to [A]sing my songs for [D]you [D]Dreams of being a country star since [G]I was only small [D]Singing to my heart's content, and learning from them [A]all I'm [D]waiting for the day each [G]band to roll into [A]town And [D]everyone would gather to [A]hear that country [D]sound Ukulele solo tab somewhere over the rainbow in the key of G with chords.

More ukulele solo tabs here . Lean On Me Solo Ukulele Tab With Chords In The Key Of G Major. More ukulele solo tabs here .

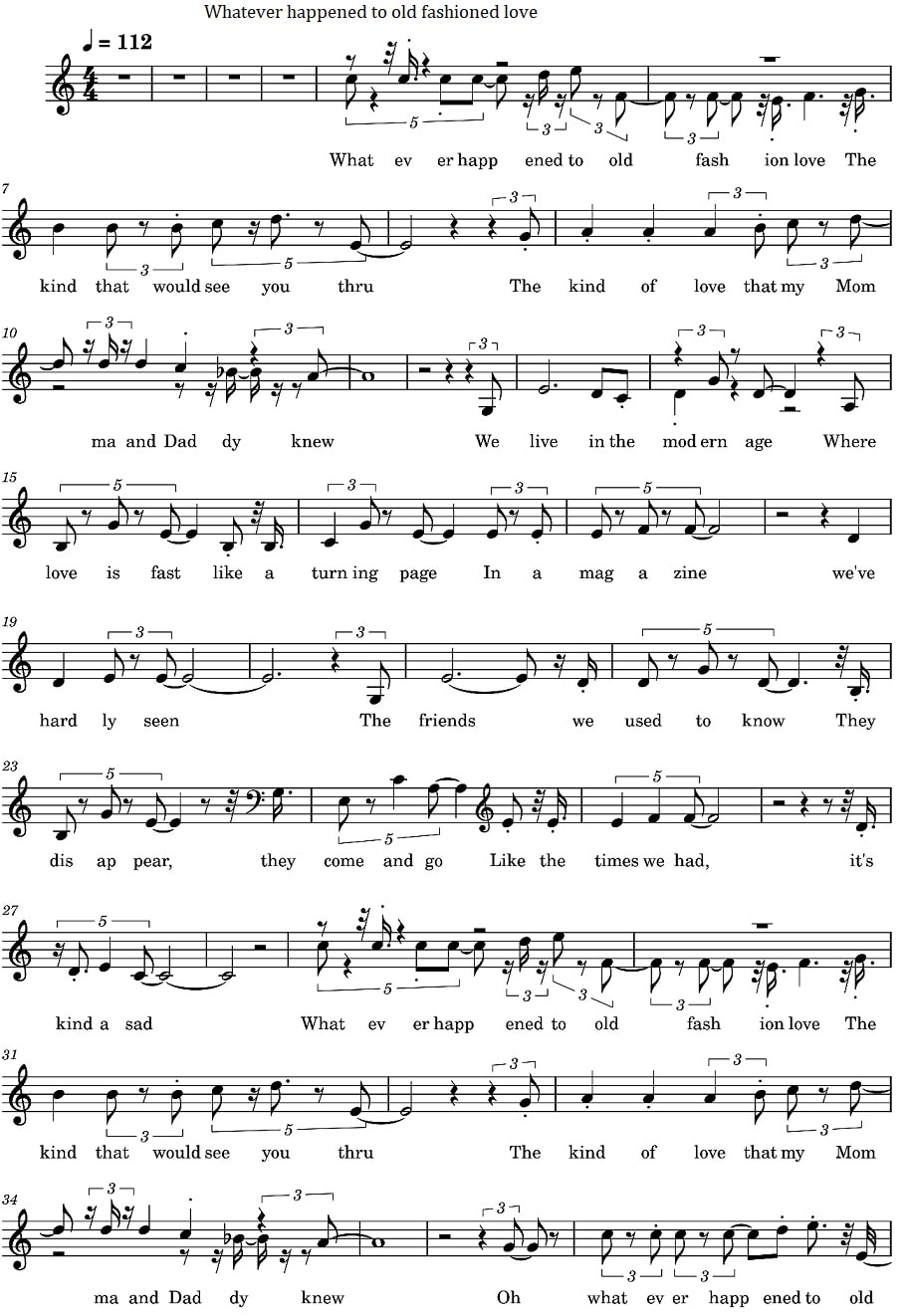

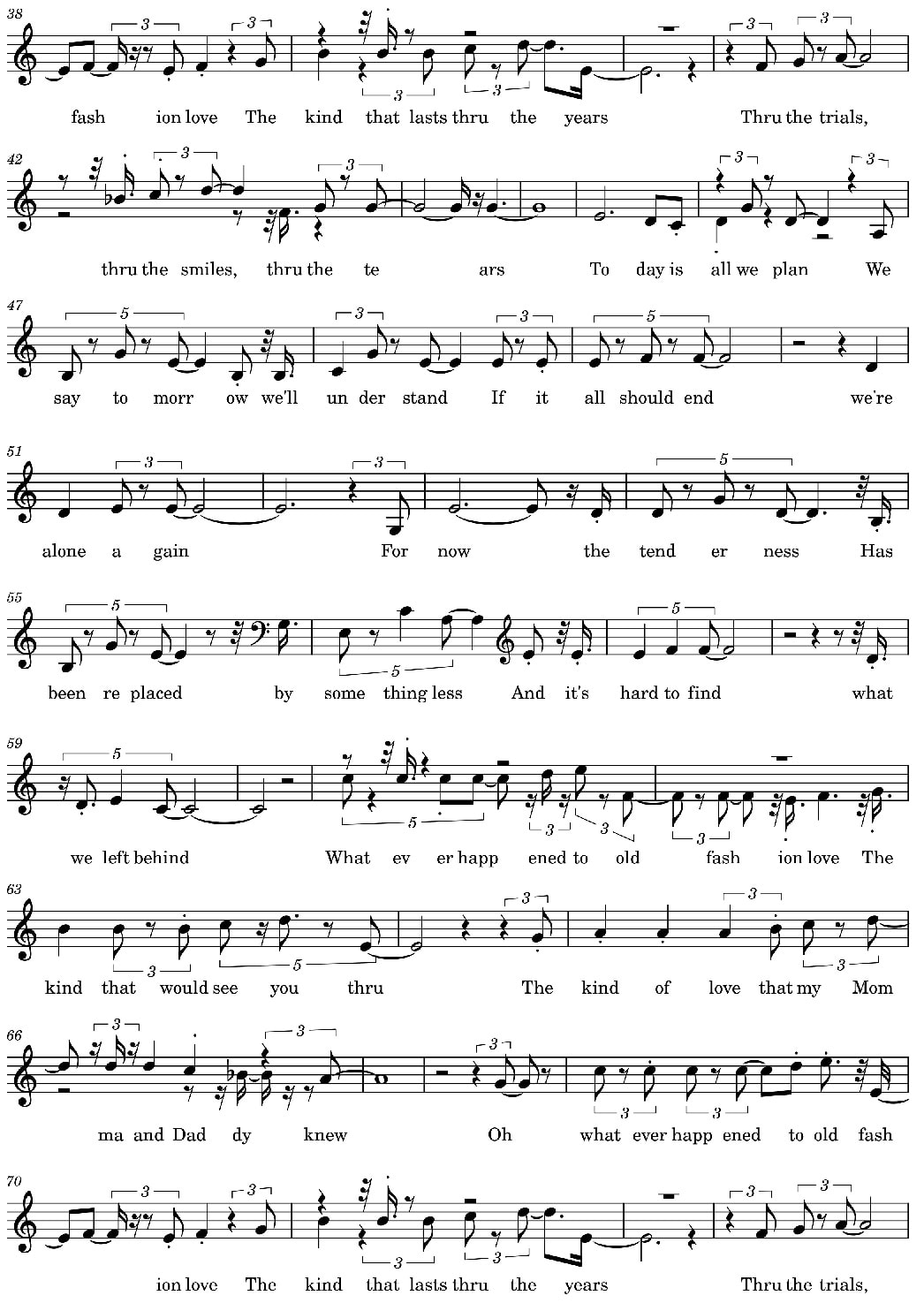

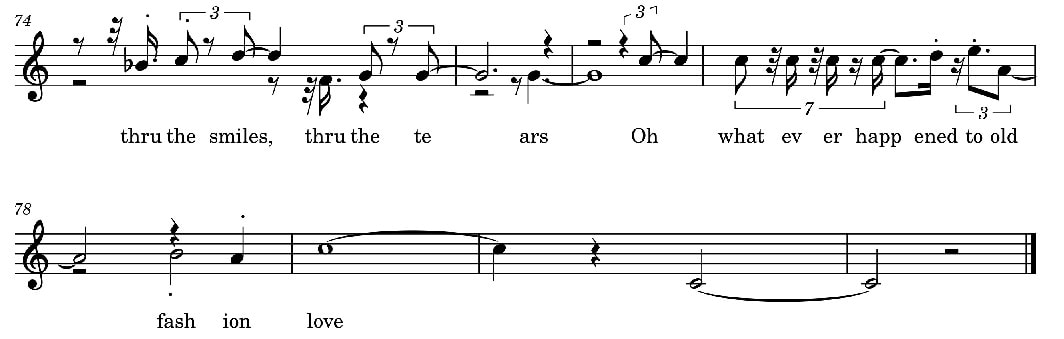

Whatever Happened To Old Fashioned Love Sheet Music By B.J. Thomas and also recorded by Irish singer Daniel O'Donnell.

|

Martin DardisIrish folk song lyrics, chords and a whole lot more Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed