The Black Velvet Band Lyrics And Guitar Chords

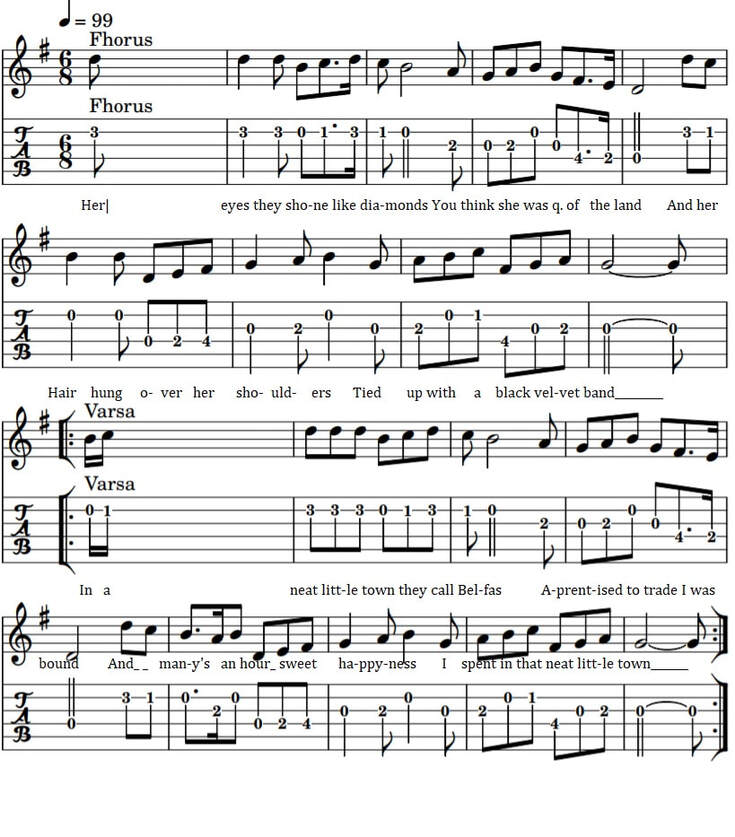

Irish folk song. Traditional.The fingerstyle [ picking ]guitar tab is included plus a version in CGDA tuning for the tenor guitar / mandola. The 5 string banjo chords for the key of G are included. Van Dieman's Land is named after the Dutchman who discovered it. Many people were transported there by the British mostly for petty crime, causing a lifetime of misery for their families. Recorded by The Dubliners [ lyrics ], The Clancy Brothers, The High Kings, The Pogues, The Irish Rovers to name a few. The guitar / ukulele chords are in the key of D in chordpro, the same version I'm playing in the youtube video. It's a very easy song to learn. The sheet music for tin whistle for the black velvet band is also included on the site. The black velvet band fingerstyle guitar tab included.

Chorus]

Her[D] eyes they shone like diamonds,you think she was queen of the[A7] land.

With her[D] hair thrown over her shoulder,tied[A] up with a black velvet[D] band.

[1]

As I went walking down Broadway,not intending to stay very long,

I met with this frolicksome damsel,as she came tripping along.

[2]

A watch she took from his pocket,and slipped it right into my hand,

On the very first day that I met her,bad luck to the black velvet band.

[3]

Before the judge and jury,next morning we had to appear,

A gentleman claimed his jewellery,and the case against us was clear,

[4]

Seven long years transportation,right down to ''Van Diemen's Land''

Far away from my friends and companions,betrayed by the black velvet band,

[Chorus after every verse]

Her[D] eyes they shone like diamonds,you think she was queen of the[A7] land.

With her[D] hair thrown over her shoulder,tied[A] up with a black velvet[D] band.

[1]

As I went walking down Broadway,not intending to stay very long,

I met with this frolicksome damsel,as she came tripping along.

[2]

A watch she took from his pocket,and slipped it right into my hand,

On the very first day that I met her,bad luck to the black velvet band.

[3]

Before the judge and jury,next morning we had to appear,

A gentleman claimed his jewellery,and the case against us was clear,

[4]

Seven long years transportation,right down to ''Van Diemen's Land''

Far away from my friends and companions,betrayed by the black velvet band,

[Chorus after every verse]

Here's the guitar chords in the key of C.

Her [C] eyes they shone like diamonds,you think she was queen of the [G7] land.

With her [C] hair thrown over her shoulder,tied [G] up with a black velvet [C] band.

Key of G

Her [G] eyes they shone like diamonds,you think she was queen of the [D7] land.

With her [G] hair thrown over her shoulder,tied [D] up with a black velvet [G] band.

Her [C] eyes they shone like diamonds,you think she was queen of the [G7] land.

With her [C] hair thrown over her shoulder,tied [G] up with a black velvet [C] band.

Key of G

Her [G] eyes they shone like diamonds,you think she was queen of the [D7] land.

With her [G] hair thrown over her shoulder,tied [D] up with a black velvet [G] band.

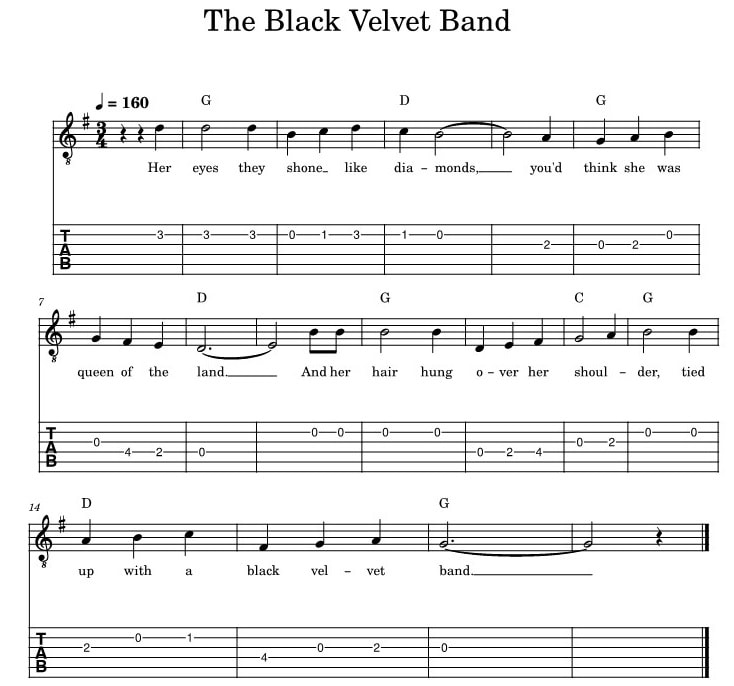

Black velvet band guitar tab in G Major

Below is the list of sheet music and tin whistle songs that are in my ebooks. This is the largest collection of tin whistle songs ever put together.[over 800 songs ] Including folk, pop and trad tunes plus German And French songs along with Christmas Carols.

All of the sheet music tabs have been made as easy to play as was possible.

The price of the ebooks is €7.50

All of the sheet music tabs have been made as easy to play as was possible.

The price of the ebooks is €7.50

More Irish folk song guitar tabs are here .

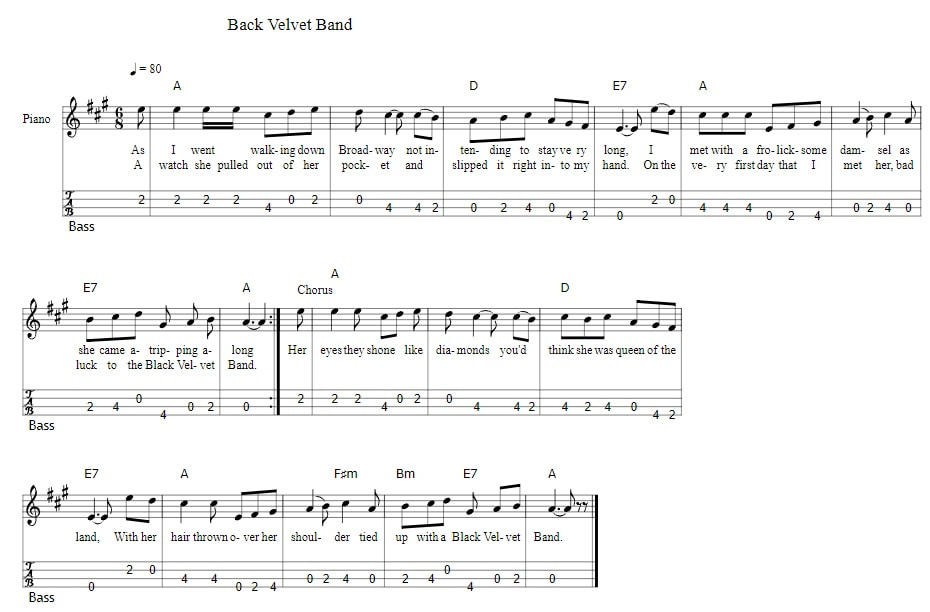

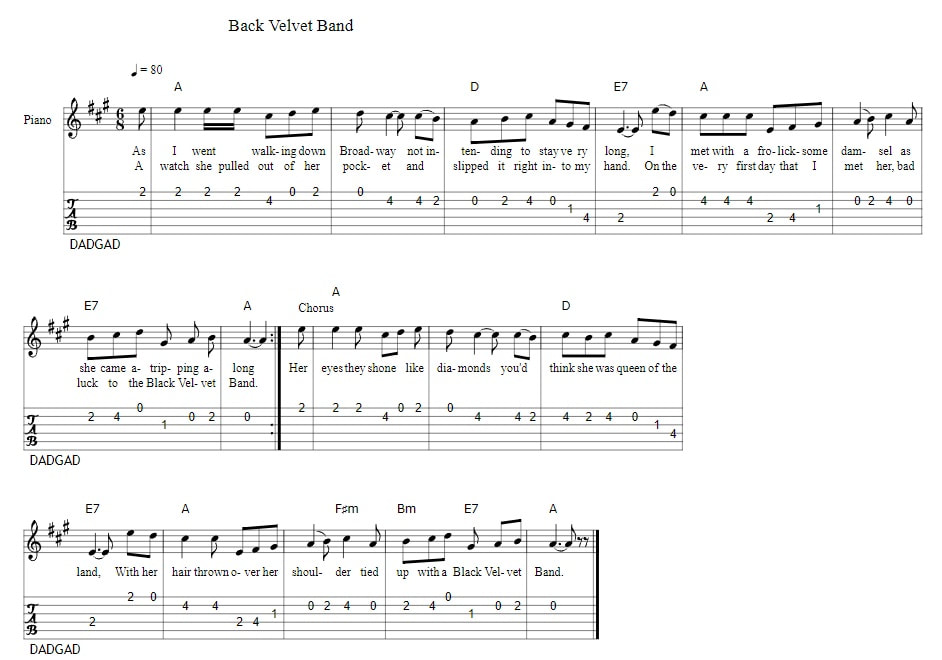

Tenor guitar / mandola tab in CGDA Tuning

The black velvet band fingerstyle guitar tab

The 5 sting banjo chords for The Black Velvet Band for the key of G Major