Bold Robert Emmet lyrics and chords

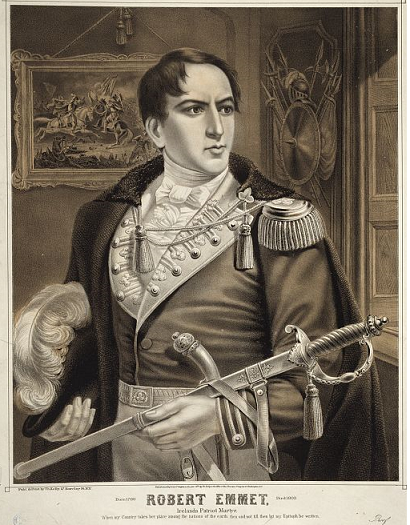

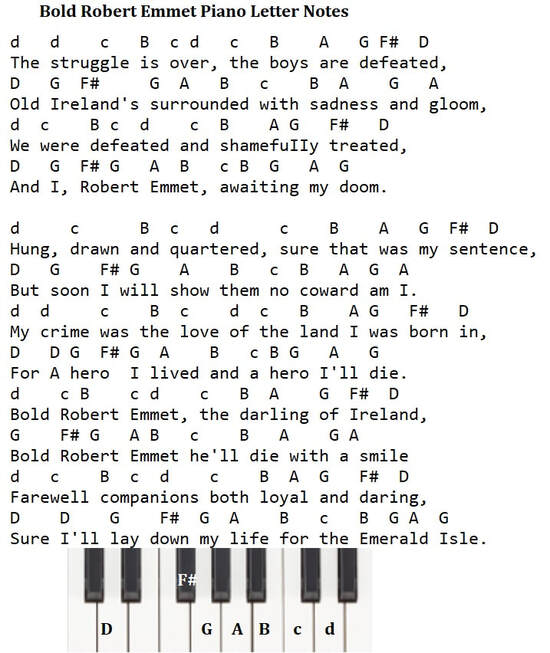

A traditional ballad recorded by The Dublin City Ramblers and The Clancy Brothers. Robert Emmet was hung drawn and quartered in Thomas Street Dublin on September 1803. The last verse of the song was written by Alan P. Barrett in 2014 and incorporates perhaps the most telling remark, from his speech from the dock. The tin whistle sheet music is included along with the piano keyboard music letter notes.

|

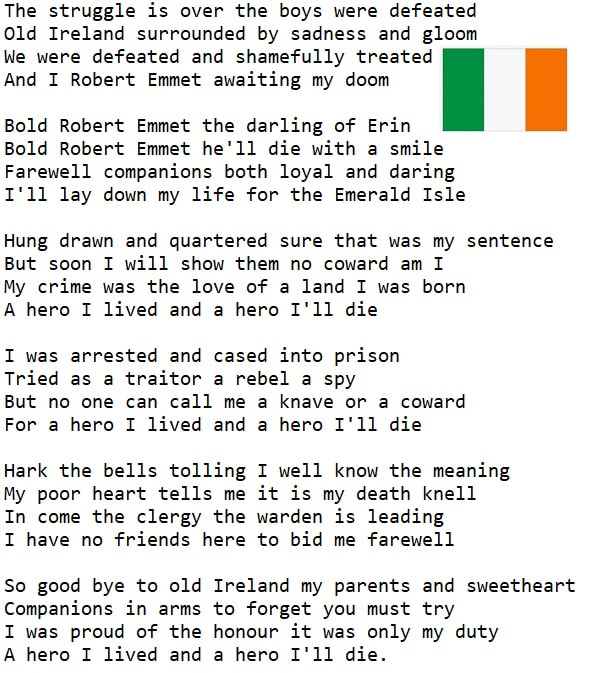

The[D] struggle is[G] over the[D] boys were de[A7]feated

Old[D] Ireland sur[A7]rounded by[D] sadness and[G] gloom We[D] were de[A7]feated and[D] shamefully[A7] treated And[D] I Robert[G] Emmet a[A7]waiting my[D] doom [Chorus] [D]Bold Robert [G]Emmet the [D]darling of [A7]Erin [D]Bold Robert [A7]Emmet he'll [D]die with a [G]smile [D]Farewell com[A7]panions both [D]loyal and [A7]daring I'll [D]lay down my [G]life for the [A7]Emerald [D]Isle Hung drawn and quartered sure that was my sentence But soon I will show them no coward am I My crime was the love of a land I was born A hero I lived and a hero I'll die I was arrested and cased into prison Tried as a traitor a rebel a spy But no one can call me a knave or a coward For a hero I lived and a hero I'll die Hark the bells tolling I well know the meaning My poor heart tells me it is my death knell In come the clergy the warden is leading I have no friends here to bid me farewell So good bye to old Ireland my parents and sweetheart Companions in arms to forget you must try I was proud of the honour it was only my duty A hero I lived and a hero I'll die. Erin, mo mhuirnin, my love and my country! Ireland, my Ireland [ song ], though dead I shall be Hear now the words of my final oration: Write me no epitaph ‘til my country is free!. Bold Robert Emmet Tin Whistle Sheet Music and letter notes. The version I worked out here is from listening to The Dublin City Ramblers. There are other pieces of sheet music around the internet and in song books but they don't even come close to the way the 'ramblers sing it. I have listened to many version of this song over the years and all are different in little ways. If you listen to Anna McGolderick's version you'll hear it been sang in a slow air and using a different tune. The Wolfe Tones use the tune that's close to the one I composed here but it's not note perfect. It was The Dublin City Ramblers version that I heard the first all them years ago so that's the tune that stayed in me head and that's the one that's included here. Youtube video lesson included, although it's fairly easy to play anyway.

|

Drawing Of Robert EmmetHere's the guitar chords for the key of G

The[G] struggle is[C] over the[G] boys were de[D7]feated Old[G] Ireland sur[D7]rounded by[G] sadness and[C] gloom We[G] were de[D7]feated and[G] shamefully[D7] treated And[G] I Robert[C] Emmet a[D7]waiting my[G] doom [G]Bold Robert [C]Emmet the [G]darling of [D7]Erin [G]Bold Robert [D7]Emmet he'll [G]die with a [C]smile [G]Farewell com[D7]panions both [G]loyal and [D7]daring I'll [G]lay down my [C]life for the [D7]Emerald [G]Isle |

Robert Emmet was SENTENCED to be hung, drawn and quartered but that was not carried out (it had become customary not to carry that sentence out in full for some time already). Accordingly he was hung and then decapitated.

Your readers may be interested to know that his famous speech from the dock (or a version of it) was recited as one of the performances at radical dinners for the rest of that century and even beyond, not just in Ireland and in the United States but in England and Scotland also.

His fame spread widely and the poet Shelley wrote a piece about him.

He is lauded in not just this popular song but also The Three Flowers by Reddin and Anne Devlin by Pete St. John.

Slán go fóill, Diarmuid Breatnach

Your readers may be interested to know that his famous speech from the dock (or a version of it) was recited as one of the performances at radical dinners for the rest of that century and even beyond, not just in Ireland and in the United States but in England and Scotland also.

His fame spread widely and the poet Shelley wrote a piece about him.

He is lauded in not just this popular song but also The Three Flowers by Reddin and Anne Devlin by Pete St. John.

Slán go fóill, Diarmuid Breatnach