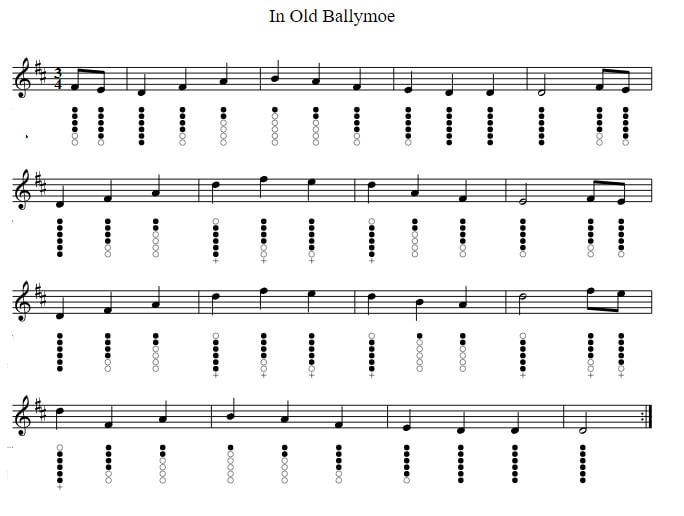

Old Ballymoe Irish Song Lyrics And Guitar Chords

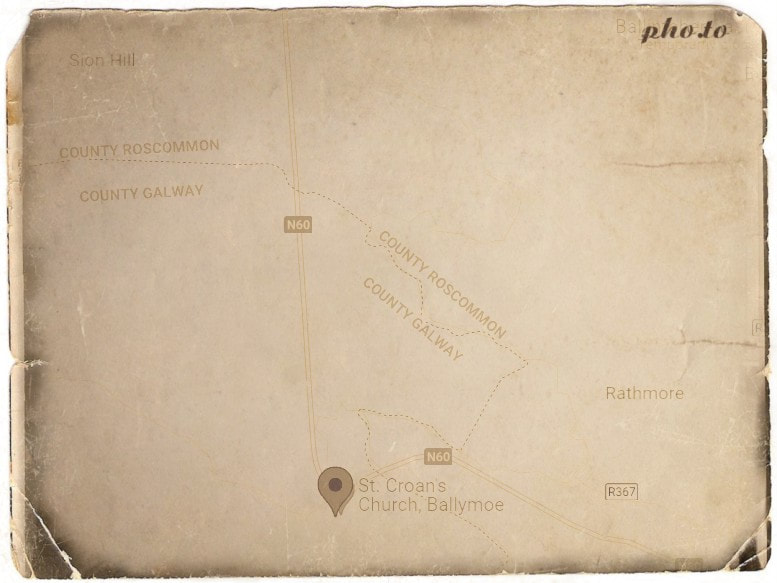

The singer in the video is Cathy Jordan. Cathy Jordan version in A major with capo on the 2nd fret.Cathy Jordan also likes to sing the old ballad Down By The Glenside .Old Ballymoe sheet music for tin whistle in D now added.

The writer remains unknown, this song was collected by Micho Russell [1915 - 1984] from Doolin County Clare who was a story teller, flute and tin whistle player. Micho became well known during the trad. revival in the 1960s. Micho was also a fine singer and had a story behind every tune he played. He preformed to audiences all over the world and made several albums. His best loved album released in 1995 ''Ireland's Whistling Ambassador'' also included a booklet about the tunes. Micho played a huge role in attracting people from all over the world to his native village of Doolin to hear traditional music played by the finest in the land. Also recorded by Annette Griffin.

|

In the (G)county Ros(C)common in (D)hailstones and (G)rain.

I was crossing the fields on the way to the (D)plane I (G)met a fair (Am)Colleen says (G)she do you (C)know What’s the (G)shortest of (Am)shortcuts into (D)Old Bally(G)moe? Says (G)I, Colleen (C)oh, who (D)led you a(G)stray. I think I’ll go with you, and show you the (D)way Says (G)she, I’m not (Am)willing, for (G)you I dun(C)noe You could (G)kiss me bet(Am)ween here and (D)Old Bally(G)moe Says (G)I, Colleen (C)oh, ?? (D)seldom ?? (G)kissed She says, poor lad, a lot you have (D)missed Says (G)I, I am (Am)willing to (G)learn, you (C)know We can (G)practice bet(Am)ween, here and (D)Old Bally(G)moe You (G)think I’d go (C)with you, you (D)moron, gar(G)rough I dont like, your looks, and your smoothering (D)blows You’re (G)young and good (Am)looking but (G)god knows your (C)slow You (G)look like you (Am)did one, in (D)Old Bally(G)moe Says (G)he I’ve been (C)noted, for (D)strength and good (G)looks My brain’s not so bad, when I’ve mastered the (D)books And (G)if you are (Am)willing, tis (G)married we’ll (C)go And for(G)ever live (Am)happy, in (D)Old Bally(G)moe She (G)started to (C)laugh, till I (D)thought she would (G)choke She says, poor lad, I will tell you a (D)joke Get (G)out of my (Am)way, for (G)now I must (C)go I’ve a (G)husband and (Am)six kids in (D)Old Bally(G)moe! Chords for the key of D

In the (D)county Ros(G)common in (A)hailstones and (D)rain. I was crossing the fields on the way to the (A)plane I (D)met a fair (Em)Colleen says (D)she do you (G)know What’s the (D)shortest of (Em)shortcuts into (A)Old Bally(D)moe? Says (D)I, Colleen (G)oh, who (A)led you a(D)stray. I think I’ll go with you, and show you the (A)way Says (D)she, I’m not (Em)willing, for (D)you I dun(G)noe You could (D)kiss me bet(Em)ween here and (A)Old Bally(D)moe Says (D)I, Colleen (G)oh, ?? (A)seldom ?? (D)kissed She says, poor lad, a lot you have (A)missed Says (D)I, I am (Em)willing to (D)learn, you (G)know We can (D)practice bet(Em)ween, here and (A)Old Bally(D)moe You (D)think I’d go (G)with you, you (A)moron, gar(D)rough I dont like, your looks, and your smoothering (A)blows You’re (D)young and good (Em)looking but (D)god knows your (G)slow You (D)look like you (Em)did one, in (A)Old Bally(D)moe Says (D)he I’ve been (G)noted, for (A)strength and good (D)looks My brain’s not so bad, when I’ve mastered the (A)books And (D)if you are (Em)willing, tis (D)married we’ll (G)go And for(D)ever live (Em)happy, in (A)Old Bally(D)moe She (D)started to (G)laugh, till I (A)thought she would (D)choke She says, poor lad, I will tell you a (A)joke Get (D)out of my (Em)way, for (D)now I must (G)go I’ve a (D)husband and (Em)six kids in (A)Old Bally(D)moe! Old Ballymoe Lyrics And Chords In C Major

In the (C)county Ros(F)common in (G)hailstones and (C)rain. I was crossing the fields on the way to the (G)plane I (C)met a fair (Dm)Colleen says (C)she do you (F)know What’s the (C)shortest of (Dm)shortcuts into (G)Old Bally(C)moe? Says (C)I, Colleen (F)oh, who (G)led you a(C)stray. I think I’ll go with you, and show you the (G)way Says (C)she, I’m not (Dm)willing, for (C)you I dun(F)noe You could (C)kiss me bet(Dm)ween here and (G)Old Bally(C)moe Says (C)I, Colleen (F)oh, ?? (G)seldom ?? (C)kissed She says, poor lad, a lot you have (G)missed Says (C)I, I am (Dm)willing to (C)learn, you (F)know We can (C)practice bet(Dm)ween, here and (G)Old Bally(C)moe You (C)think I’d go (F)with you, you (G)moron, gar(C)rough I dont like, your looks, and your smoothering (G)blows You’re (C)young and good (Dm)looking but (C)god knows your (F)slow You (C)look like you (Dm)did one, in (G)Old Bally(C)moe Says (C)he I’ve been (F)noted, for (G)strength and good (C)looks My brain’s not so bad, when I’ve mastered the (G)books And (C)if you are (Dm)willing, tis (C)married we’ll (F)go And for(C)ever live (Dm)happy, in (G)Old Bally(C)moe She (C)started to (F)laugh, till I (G)thought she would (C)choke She says, poor lad, I will tell you a (G)joke Get (C)out of my (Dm)way, for (C)now I must (F)go I’ve a (C)husband and (Dm)six kids in (G)Old Bally(C)moe! |

|