Hot Asphalt Lyrics And Chords

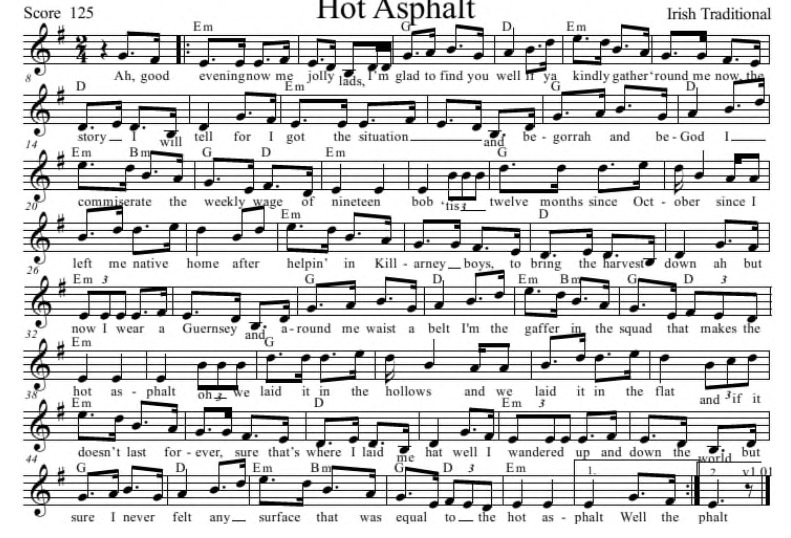

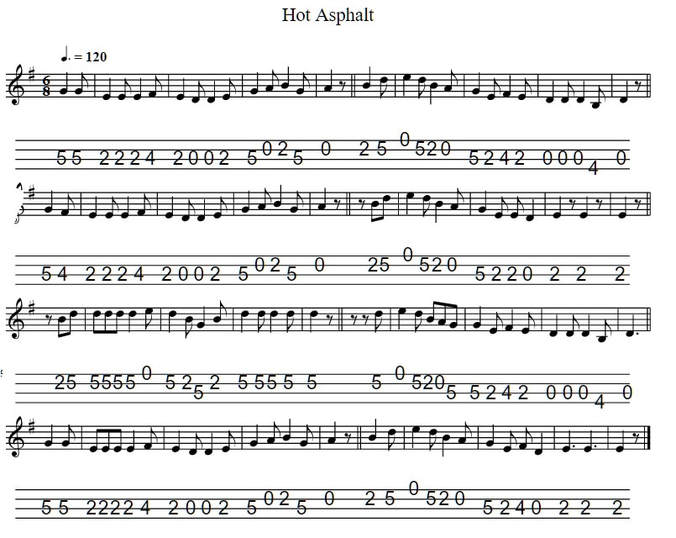

The sheet music /tin whistle tab for Hot Asphalt is in the Dubliners ebook of tabs

The sheet music and mandolin / banjo tab is included.The Dubliners. Another similar that was also sang by the late Luke Kelly is England's Motorway Song. - This folk song is credited to Ewan McColl, although Ewan did not write the original , which dates back to 1880's , this is his version, I'm sure the tune is Scottish, Anyway The Dubliners made it famous again, fair play' with Luke Kelly singing, Ronnie Drew on Guitar John Sheehan on fiddle and Barney McKenna on banjo. The second set of guitar chords are the one's that are played on the Dubliners youtube version. Also recorded by The Corries, The Wolfe Tones, The Pogues and The Dublin City Ramblers, Irish singer George Murphy, The Mary Wallopers. The youtube video is by The Dubliners [ lyrics ].

Hot Asphalt is a traditional folk song with a long history and deep roots in the Irish and Celtic music traditions. It has been sung and passed down through generations, evolving and adapting over time, yet still retaining its powerful and timeless message.

The song has a simple, yet captivating melody and lyrics that tell a story of love, heartache, and the harsh realities of life. It has been recorded by numerous artists, both in its traditional form and in more modern interpretations, making it a beloved and versatile piece of music that continues to resonate with audiences today.

The origins of Hot Asphalt can be traced back to Ireland in the 19th century, where it was known as a street ballad sung by Irish laborers. These workers, often immigrants and marginalized in society, would sing the song as they toiled in construction and road building, using the familiar tune and lyrics to lift their spirits and pass the time. This is reflected in the song's chorus, which declares, 'I'm off to work on the railroad, with pick and shovel in my hand.'

The lyrics of Hot Asphalt tell the story of a young man who leaves his true love behind to seek work on the railroad, leaving her with a promise to return when he has made enough money. However, as he travels and works, he encounters many temptations and distractions, eventually succumbing to the 'hot asphalt' of the title – a metaphor for the allure of the city and its vices. The song's narrator reflects on his actions, regretting the choices he made and the pain he has caused his loved one.

The themes of love, loss, and temptation in the song are universal and have resonated with audiences for centuries. The longing for a better life and the sacrifices one must make to achieve it are sentiments that are still relevant today. Hot Asphalt captures the struggles and dreams of the working class, as well as the harsh realities of leaving loved ones behind for the pursuit of a better future.

Over the years, Hot Asphalt has been recorded by various artists, each adding their own unique flair to the song. One of the earliest known recordings is by Irish folk singer Margaret Barry, who recorded the song in the 1950s. Since then, it has been covered by renowned musicians such as The Dubliners with Luke Kelly on Vocals, The Clancy Brothers, to name a few. The song has also been adapted by contemporary artists, such as Irish-American group Solas, who infused it with a modern twist while still staying true to its traditional roots.

The song has a simple, yet captivating melody and lyrics that tell a story of love, heartache, and the harsh realities of life. It has been recorded by numerous artists, both in its traditional form and in more modern interpretations, making it a beloved and versatile piece of music that continues to resonate with audiences today.

The origins of Hot Asphalt can be traced back to Ireland in the 19th century, where it was known as a street ballad sung by Irish laborers. These workers, often immigrants and marginalized in society, would sing the song as they toiled in construction and road building, using the familiar tune and lyrics to lift their spirits and pass the time. This is reflected in the song's chorus, which declares, 'I'm off to work on the railroad, with pick and shovel in my hand.'

The lyrics of Hot Asphalt tell the story of a young man who leaves his true love behind to seek work on the railroad, leaving her with a promise to return when he has made enough money. However, as he travels and works, he encounters many temptations and distractions, eventually succumbing to the 'hot asphalt' of the title – a metaphor for the allure of the city and its vices. The song's narrator reflects on his actions, regretting the choices he made and the pain he has caused his loved one.

The themes of love, loss, and temptation in the song are universal and have resonated with audiences for centuries. The longing for a better life and the sacrifices one must make to achieve it are sentiments that are still relevant today. Hot Asphalt captures the struggles and dreams of the working class, as well as the harsh realities of leaving loved ones behind for the pursuit of a better future.

Over the years, Hot Asphalt has been recorded by various artists, each adding their own unique flair to the song. One of the earliest known recordings is by Irish folk singer Margaret Barry, who recorded the song in the 1950s. Since then, it has been covered by renowned musicians such as The Dubliners with Luke Kelly on Vocals, The Clancy Brothers, to name a few. The song has also been adapted by contemporary artists, such as Irish-American group Solas, who infused it with a modern twist while still staying true to its traditional roots.

Here are the guitar chords as played by The Dubliners on the youtube video. They are only slightly different than the chords above.

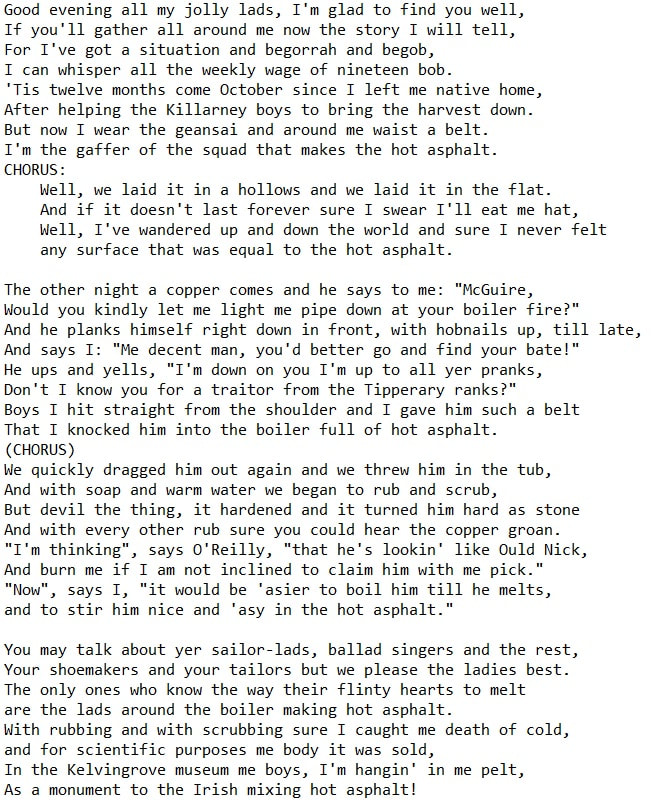

Good [Em]evening all my jolly lads, I'm glad to find you [D]well,

If you'll g[Em]ather all around me now the st[D]ory I will tell,

For I've g[Em]ot a situation and beg[G]orrah and beg[D]ob,

I can wh[Em]isper all the weekly wage of n[Em]ineteen bob.

'Tis tw[G]elve months come October since I left me native home,

After helping the Killarney boys to [D]bring the harvest down.

But n[Em]ow I wear the geansai and around me waist a [D]belt.

I'm the g[Em]affer of the squad that makes the hot asphalt.

CHORUS:

Well, we [G]laid it in a hollows and we laid it in the flat.

And if it doesn't last forever sure I [D]swear I'll eat me hat,

Well, I've [Em]wandered up and down the world and sure I never [D]felt

any s[Em]urface that was equal to the hot asphalt.

Good [Em]evening all my jolly lads, I'm glad to find you [D]well,

If you'll g[Em]ather all around me now the st[D]ory I will tell,

For I've g[Em]ot a situation and beg[G]orrah and beg[D]ob,

I can wh[Em]isper all the weekly wage of n[Em]ineteen bob.

'Tis tw[G]elve months come October since I left me native home,

After helping the Killarney boys to [D]bring the harvest down.

But n[Em]ow I wear the geansai and around me waist a [D]belt.

I'm the g[Em]affer of the squad that makes the hot asphalt.

CHORUS:

Well, we [G]laid it in a hollows and we laid it in the flat.

And if it doesn't last forever sure I [D]swear I'll eat me hat,

Well, I've [Em]wandered up and down the world and sure I never [D]felt

any s[Em]urface that was equal to the hot asphalt.

Good [Em]evening all my jolly lads, I'm [G]glad to find you [D]well,

If you'll g[Em]ather all around me now the st[D]ory I will tell,

For I've g[Em]ot a situation and beg[G]orrah and beg[D]ob,

I can wh[Em]isper all the weekly w[D]age of n[Em]ineteen bob.

'Tis tw[G]elve months come October since I l[G]eft me native home,

After h[Em]elping the Killarney boys to br[D]ing the harvest down.

But n[Em]ow I wear the geansai and ar[G]ound me waist a b[D]elt.

I'm the g[Em]affer of the squad that m[D]akes the h[Em]ot asphalt.

CHORUS:

Well, we l[G]aid it in a hollows and we l[G]aid it in the flat.

And if it d[Em]oesn't last forever sure I sw[D]ear I'll eat me hat,

Well, I've w[Em]andered up and down the world and s[G]ure I never f[D]elt

any s[Em]urface that was equal t[D]o the h[Em]ot asphalt.

The other night a copper comes and he says to me: "McGuire,

Would you kindly let me light me pipe down at your boiler fire?"

And he planks himself right down in front, with hobnails up, till late,

And says I: "Me decent man, you'd better go and find your bate!"

He ups and yells, "I'm down on you I'm up to all yer pranks,

Don't I know you for a traitor from the Tipperary ranks?"

Boys I hit straight from the shoulder and I gave him such a belt

That I knocked him into the boiler full of hot asphalt.

(CHORUS)

We quickly dragged him out again and we threw him in the tub,

And with soap and warm water we began to rub and scrub,

But devil the thing, it hardened and it turned him hard as stone

And with every other rub sure you could hear the copper groan.

"I'm thinking", says O'Reilly, "that he's lookin' like Ould Nick,

And burn me if I am not inclined to claim him with me pick."

"Now", says I, "it would be 'asier to boil him till he melts,

and to stir him nice and 'asy in the hot asphalt."

(CHORUS)

You may talk about yer sailor-lads, ballad singers and the rest,

Your shoemakers and your tailors but we please the ladies best.

The only ones who know the way their flinty hearts to melt

are the lads around the boiler making hot asphalt.

With rubbing and with scrubbing sure I caught me death of cold,

and for scientific purposes me body it was sold,

In the Kelvingrove museum me boys, I'm hangin' in me pelt,

As a monument to the Irish mixing hot asphalt!

If you'll g[Em]ather all around me now the st[D]ory I will tell,

For I've g[Em]ot a situation and beg[G]orrah and beg[D]ob,

I can wh[Em]isper all the weekly w[D]age of n[Em]ineteen bob.

'Tis tw[G]elve months come October since I l[G]eft me native home,

After h[Em]elping the Killarney boys to br[D]ing the harvest down.

But n[Em]ow I wear the geansai and ar[G]ound me waist a b[D]elt.

I'm the g[Em]affer of the squad that m[D]akes the h[Em]ot asphalt.

CHORUS:

Well, we l[G]aid it in a hollows and we l[G]aid it in the flat.

And if it d[Em]oesn't last forever sure I sw[D]ear I'll eat me hat,

Well, I've w[Em]andered up and down the world and s[G]ure I never f[D]elt

any s[Em]urface that was equal t[D]o the h[Em]ot asphalt.

The other night a copper comes and he says to me: "McGuire,

Would you kindly let me light me pipe down at your boiler fire?"

And he planks himself right down in front, with hobnails up, till late,

And says I: "Me decent man, you'd better go and find your bate!"

He ups and yells, "I'm down on you I'm up to all yer pranks,

Don't I know you for a traitor from the Tipperary ranks?"

Boys I hit straight from the shoulder and I gave him such a belt

That I knocked him into the boiler full of hot asphalt.

(CHORUS)

We quickly dragged him out again and we threw him in the tub,

And with soap and warm water we began to rub and scrub,

But devil the thing, it hardened and it turned him hard as stone

And with every other rub sure you could hear the copper groan.

"I'm thinking", says O'Reilly, "that he's lookin' like Ould Nick,

And burn me if I am not inclined to claim him with me pick."

"Now", says I, "it would be 'asier to boil him till he melts,

and to stir him nice and 'asy in the hot asphalt."

(CHORUS)

You may talk about yer sailor-lads, ballad singers and the rest,

Your shoemakers and your tailors but we please the ladies best.

The only ones who know the way their flinty hearts to melt

are the lads around the boiler making hot asphalt.

With rubbing and with scrubbing sure I caught me death of cold,

and for scientific purposes me body it was sold,

In the Kelvingrove museum me boys, I'm hangin' in me pelt,

As a monument to the Irish mixing hot asphalt!

Sheet music for Hot Asphalt

Below is the banjo / mandolin tab which is basically the same as the sheet music above