Her Mantle So Green Song Lyrics And Chords

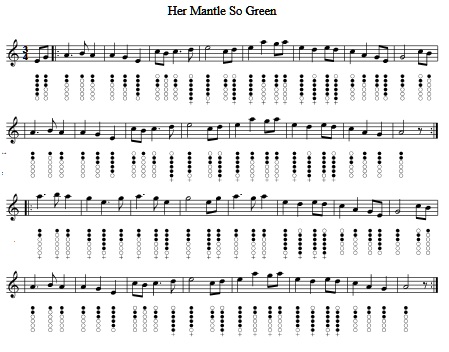

(Traditional Irish Song) Guitar chords in chordpro style fit Sinead O’Connor’s version of this beautiful song. Also included are the tin whistle sheet music notes included.

The Butcher Boy Song is another of Sinead O'Connor's '' Folk '' songs that she covered very well.

The Butcher Boy Song is another of Sinead O'Connor's '' Folk '' songs that she covered very well.

Her Mantle So Greet Song Lyrics And Chords In The Key Of C Major

Intro: C-F-Dm-Am-Am F-C-F-C-C F-C-F-C-C G7---Am-F-Dm-Am-(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

As (C)I went out (F)walking, one (Dm)morning in (Am)June -Am

To (F)view the fair (C)fields, and the (F)valleys in (C)bloom; -C

I (F)spied a pretty (C)fair maid, she a(F)ppeared like a (C)queen, -C

(G7)With - her (Am)costly fine (F)robes and her (Dm)mantle so (Am)green

(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

Says (C)I, my pretty (F)fair maid, won’t (Dm)you come with (Am)me, -Am

We'll (F)both join in (C)wedlock, and (F)married we'll (C)be; -C

I will (F)dress you in fine (C)linen, you'll a(F)ppear like a (C)queen, -C

(G7)With - your (Am)costly fine (F)robes and your (Dm)mantle so (Am)green.

(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

Says (C)she, now my (F)young man, you (Dm)must be ex(Am)cused, -Am

For (F)I'll wed with no (C)man, so you (F)must be re(C)fused; -C

To the (F)green woods I will (C)wander and (F)shun all men's (C)view -C

(G7)For - the (Am)boy I love (F)dearly lies in (Dm)famed Water(Am)loo.

Bridge: F-C-F-C-C F-C-F-C-C G7---Am-F-Dm-Am-(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

Well, (C)if you're not (F)married, say (Dm)your lover's (Am)name -Am

I (F)fought in that (C)battle, so I (F)might know the (C)same. -C

Draw (F)near to my (C)garment, and (F)there you will (C)see -C

(G7)His – (Am)name is em(F)broidered on my (Dm)mantle so (Am)green.

(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

In the (C)ribbon of her (F)mantle, there (Dm)I did be(Am)hold, -Am

His (F)name and his (C)surname, in (F)letters of (C)gold -C

Young (F)William O'(C)Riley, a(F)ppeared in my (C)view -C

(G7)He – (Am)was my chief (F)comrade back in (Dm)famed Water(Am)loo

(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

And (C)as he lay (F)dying, I (Dm)heard his last (Am)cry -Am

’If you were (F)here lovely (C)Nancy I'd be (F)willing to (C)die’ -C�

And as I (F)told her this (C)story, in (F)anguish she (C)flew, -C

(G7)And - the (Am)more that I (F)told her, the (Dm)paler she (Am)grew

(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

So I (C)smiled on my (F)Nancy, 'twas (Dm)I broke your (Am)heart, -Am

In (F)your fathers (C)garden, that (F)day we did (C)part -C

And (F)this is the (C)truth, and the (F)truth I de(C)clare, -C

(G7)Oh – (Am)here's your love (F)token the (Dm)gold ring I (Am)wear.

Irish song lyrics G-J

Intro: C-F-Dm-Am-Am F-C-F-C-C F-C-F-C-C G7---Am-F-Dm-Am-(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

As (C)I went out (F)walking, one (Dm)morning in (Am)June -Am

To (F)view the fair (C)fields, and the (F)valleys in (C)bloom; -C

I (F)spied a pretty (C)fair maid, she a(F)ppeared like a (C)queen, -C

(G7)With - her (Am)costly fine (F)robes and her (Dm)mantle so (Am)green

(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

Says (C)I, my pretty (F)fair maid, won’t (Dm)you come with (Am)me, -Am

We'll (F)both join in (C)wedlock, and (F)married we'll (C)be; -C

I will (F)dress you in fine (C)linen, you'll a(F)ppear like a (C)queen, -C

(G7)With - your (Am)costly fine (F)robes and your (Dm)mantle so (Am)green.

(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

Says (C)she, now my (F)young man, you (Dm)must be ex(Am)cused, -Am

For (F)I'll wed with no (C)man, so you (F)must be re(C)fused; -C

To the (F)green woods I will (C)wander and (F)shun all men's (C)view -C

(G7)For - the (Am)boy I love (F)dearly lies in (Dm)famed Water(Am)loo.

Bridge: F-C-F-C-C F-C-F-C-C G7---Am-F-Dm-Am-(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

Well, (C)if you're not (F)married, say (Dm)your lover's (Am)name -Am

I (F)fought in that (C)battle, so I (F)might know the (C)same. -C

Draw (F)near to my (C)garment, and (F)there you will (C)see -C

(G7)His – (Am)name is em(F)broidered on my (Dm)mantle so (Am)green.

(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

In the (C)ribbon of her (F)mantle, there (Dm)I did be(Am)hold, -Am

His (F)name and his (C)surname, in (F)letters of (C)gold -C

Young (F)William O'(C)Riley, a(F)ppeared in my (C)view -C

(G7)He – (Am)was my chief (F)comrade back in (Dm)famed Water(Am)loo

(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

And (C)as he lay (F)dying, I (Dm)heard his last (Am)cry -Am

’If you were (F)here lovely (C)Nancy I'd be (F)willing to (C)die’ -C�

And as I (F)told her this (C)story, in (F)anguish she (C)flew, -C

(G7)And - the (Am)more that I (F)told her, the (Dm)paler she (Am)grew

(Am-F)-Am-(Am-G7)

So I (C)smiled on my (F)Nancy, 'twas (Dm)I broke your (Am)heart, -Am

In (F)your fathers (C)garden, that (F)day we did (C)part -C

And (F)this is the (C)truth, and the (F)truth I de(C)clare, -C

(G7)Oh – (Am)here's your love (F)token the (Dm)gold ring I (Am)wear.

Irish song lyrics G-J