Ballinderry Song Lyrics And Chords, Irish Folk Song

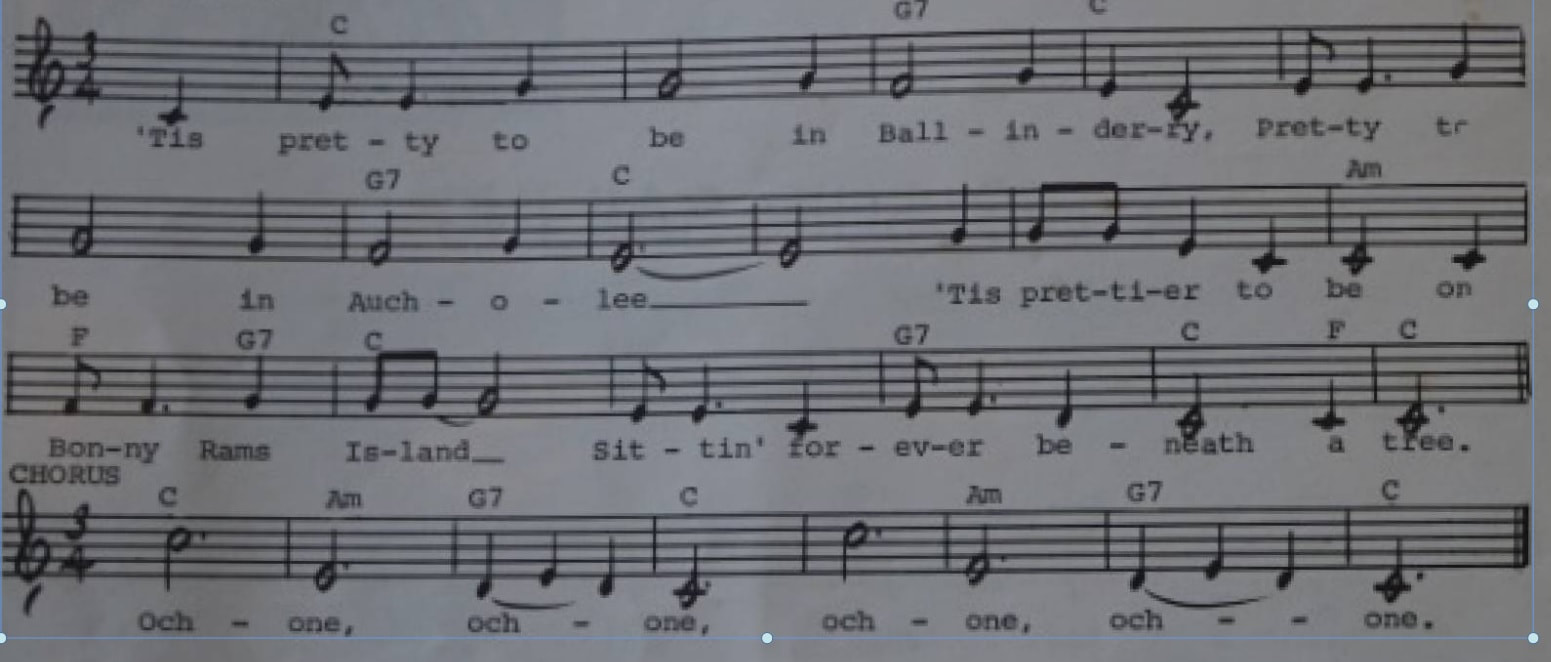

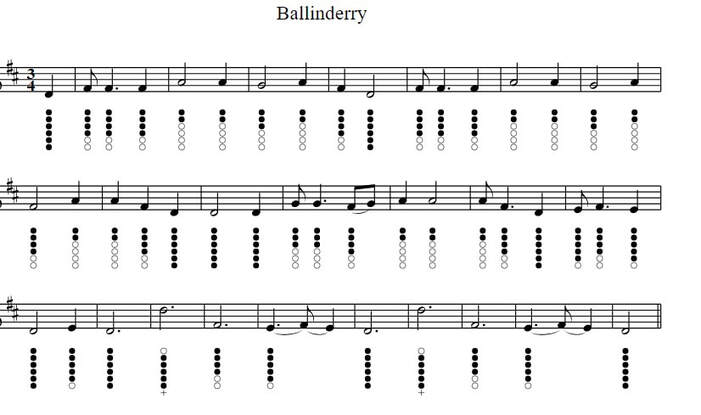

A Traditional folk song about Ballinderry. Recorded by Tommy Makem and first published by Edward Bunting 1809. Recorded by The Cottars. I have given the guitar chords in the keys of D and G.Ballinderry sheet music and tin whistle notes in D now included.

[D]Tis [G]pretty to[D] be [G]in [A]Ballin[D]derry,

[G]Pretty [D]to [G]be in [A]Aucho[D]lee*

'Tis prettier to[G] be on bonny Ram's Island

A-[D]sitting for[A]ever be[D]neath a tree.

Ochone, ochone

Ochone, ochone.

For often I sailed to bonny Ram's Island,

Arm in arm with Phelim, my demon.**

He would whistle and I would sing,

And we would make the whole island ring.

Ochone, ochone

Ochone, ochone.

I'm going," he said, "from bonny Ram's Island

Out and across the deep blue sea,

And if in your heart you love me, Mary,

Open your arms at last to me."

Ochone, ochone

Ochone, ochone.

'

Twas pretty to be in Ballinderry

But now it's as sad as sad can be,

For the ship that sailed with Phelim, my demon,

Is sunk forever beneath the sea.

Ochone, ochone

Ochone, ochone.

Here's the guitar chords in the key of G.

[G]Tis [C]pretty to[G] be [C]in [D]Ballin[G]derry,

[C]Pretty [G]to [C]be in [D]Aucho[G]lee*

'Tis prettier to[C] be on bonny Ram's Island

A-[G]sitting for[D]ever be[G]neath a tree.

Ochone, ochone

Ochone, ochone.

[G]Tis [C]pretty to[G] be [C]in [D]Ballin[G]derry,

[C]Pretty [G]to [C]be in [D]Aucho[G]lee*

'Tis prettier to[C] be on bonny Ram's Island

A-[G]sitting for[D]ever be[G]neath a tree.

Ochone, ochone

Ochone, ochone.